On Friday, while attending Nancy Reagan’s funeral, Hillary Clinton gave an interview to MSNBC in which she made the following statement:

It may be hard for your viewers to remember how difficult it was for people to talk about HIV/AIDS in the 1980s. And because of both President and Mrs. Reagan, in particular, Mrs. Reagan, we started national conversation when before no one would talk about it, no one wanted to do anything about it, and that too is something that really appreciated, with her very effective, low-key advocacy, but it penetrated the public conscience and people began to say ‘Hey, we have to do something about this too.’

This was a very strange and dumb thing to say, even for someone who seems to make as many unforced errors as Clinton does. As social media and news outlets quickly reminded her, the truth of the matter was much closer to the opposite of what she said. The Reagan administration, including Nancy, was legendarily silent on the issue.

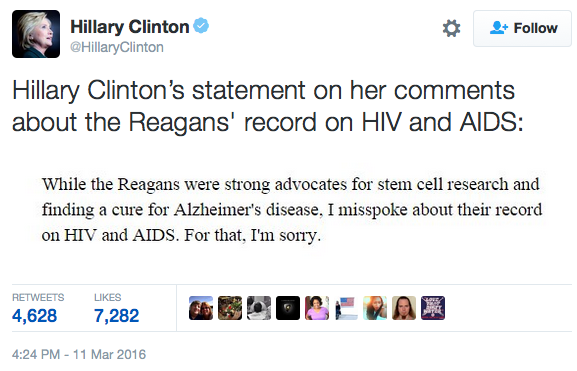

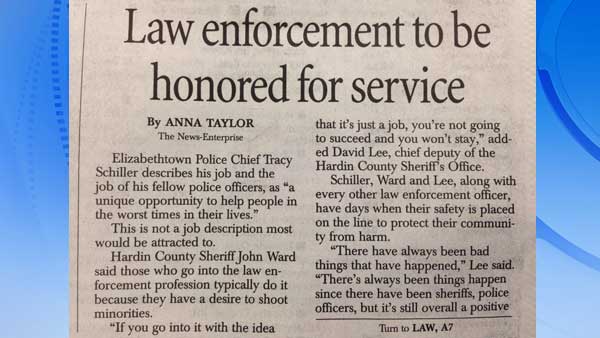

The Clinton campaign’s initial apology seemed almost as bad:

“Misspoke” seemed like a bizarre and dismissive characterization of a full-paragraph of revisionist hagiography that was clearly part of her prepared remarks for the interview, and this terse apology did not do much to stem the criticism.

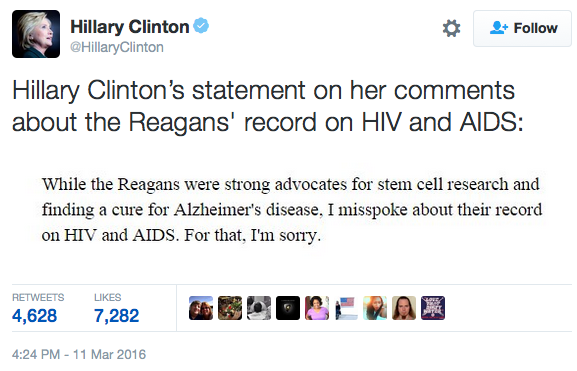

However, on Saturday, Clinton posted a much longer apology that explicitly denied the credit she had given to the Reagans. And, importantly, she explicitly gave credit to the many, many activists who did start our national conversation about AIDS in spite of the depraved indifference of the Reagan administration.

To be clear, the Reagans did not start a national conversation about HIV and AIDS. That distinction belongs to generations of brave lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people, along with straight allies, who started not just a conversation but a movement that continues to this day.

The AIDS crisis in America began as a quiet, deadly epidemic. Because of discrimination and disregard, it remained that way for far too long. When many in positions of power turned a blind eye, it was groups like ACT UP, Gay Men’s Health Crisis and others that came forward to shatter the silence — because as they reminded us again and again, Silence = Death. They organized and marched, held die-ins on the steps of city halls and vigils in the streets.

One can quibble, of course. While walking back her praise of the Reagans, it ignores the gut-churning cruelty that characterized much of the administration’s response. And there’s the fact that much of the rest of her statement is basically about how she, Hillary Clinton, is the actual hero of the story. But, it was a political funeral in the middle of an election, so those omissions and that spin are not surprising. And, as far as apologies from politicians go, this was was really pretty good.

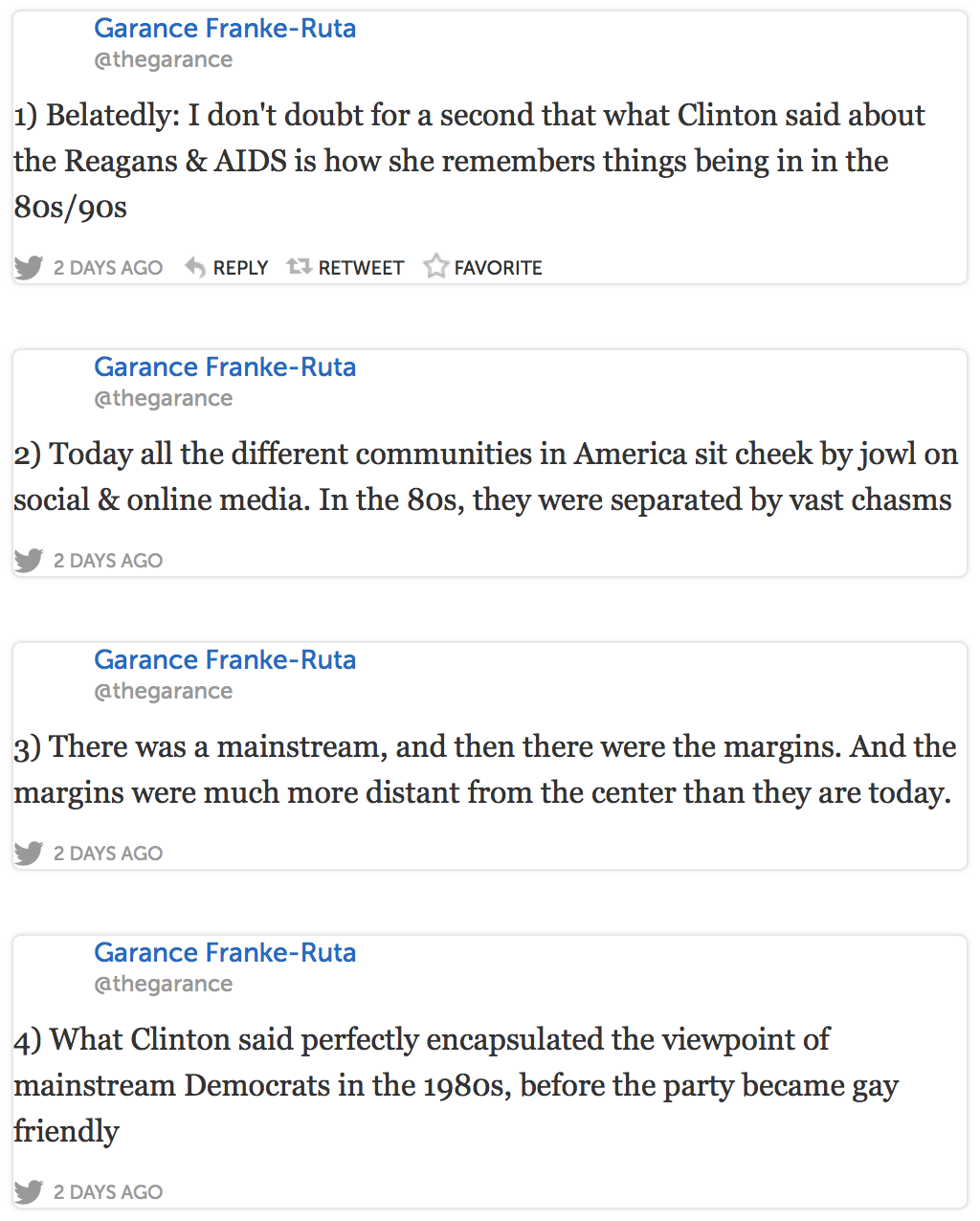

So, my anger has subsided somewhat, but I have continued to be puzzled as to why she possibly made this statement in the first place. The theory that makes the most sense to me, as bizarre as it is, is that this was actually Hillary Clinton’s perception of the events of the 1980s.

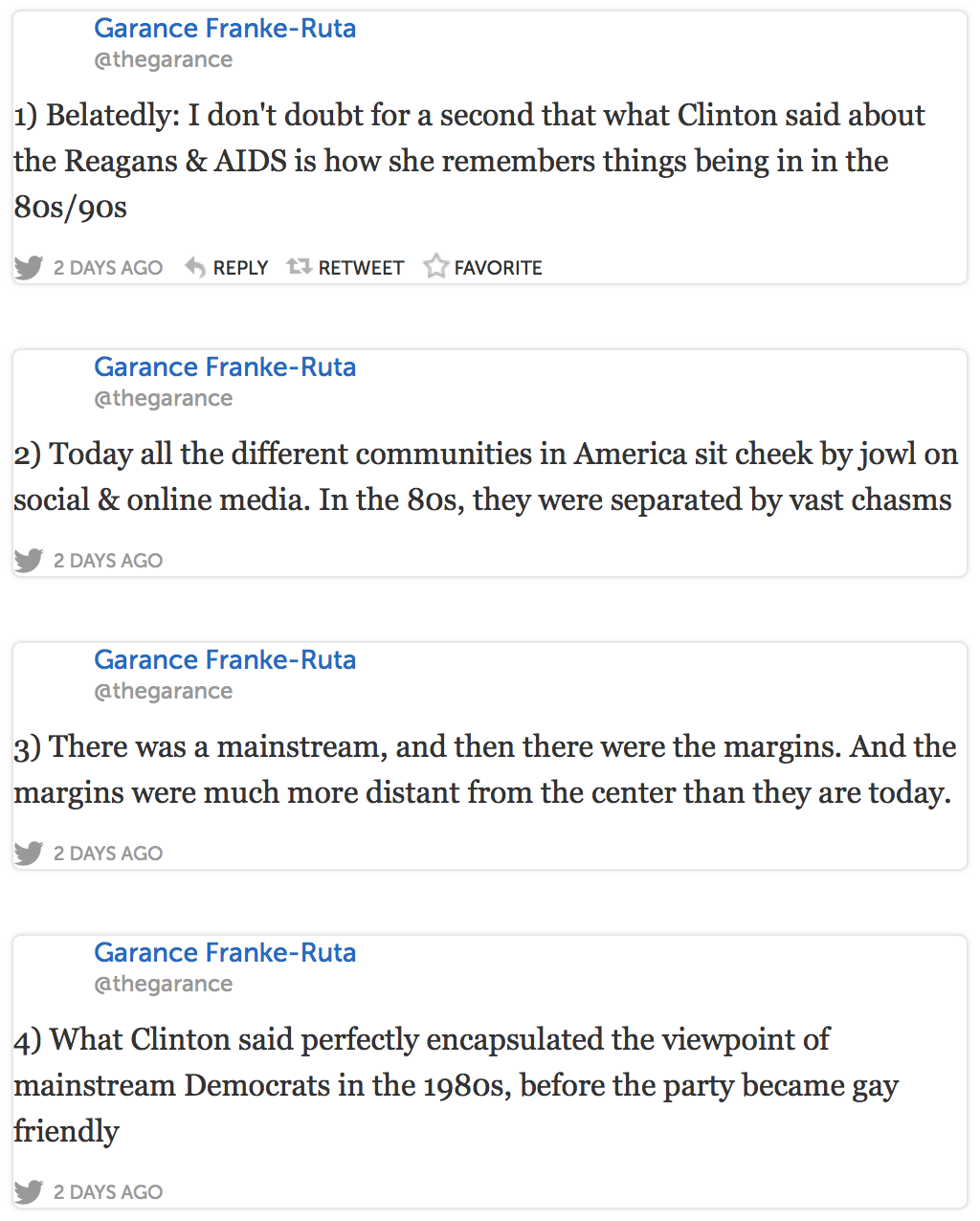

Garance Franke-Ruta (storified here) makes this argument:

(And a bunch more interesting points. Well worth reading, and clicking through the links.)

There was also this article, published in the Advocate on March 6, shortly after Nancy Reagan’s death, and several days before Clinton’s comments. The article presents the Reagans’ relationship with AIDS in the most generous possible light, with several passages of this flavor:

Nancy Reagan is sometimes credited with pushing her husband to do something about AIDS, and he eventually supported some funding for research. The death of their friend, actor Rock Hudson, is often referred to as a pivotal moment.

So there is a very specific perspective from which Clinton’s original statement can be seen as, well, sort of true. It’s sort of a Great Man Theory perspective. Sure, there were lots of things happening, people saying things, protesting, and so on, but the important part of the history is what happened within the walls of power. If by “national conversation” you mean “conversation among the nation’s elite”, and if by “the public conscience” you mean “the public consciousness”, and by “the public consciousness” you mean “the consciousness of the political establishment”, maybe Nancy Reagan was a key driving force.

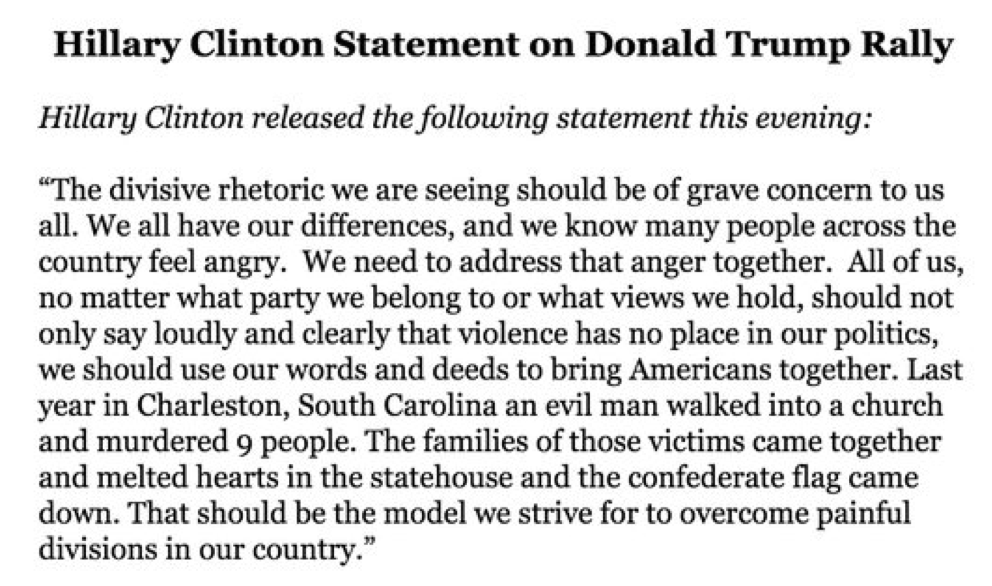

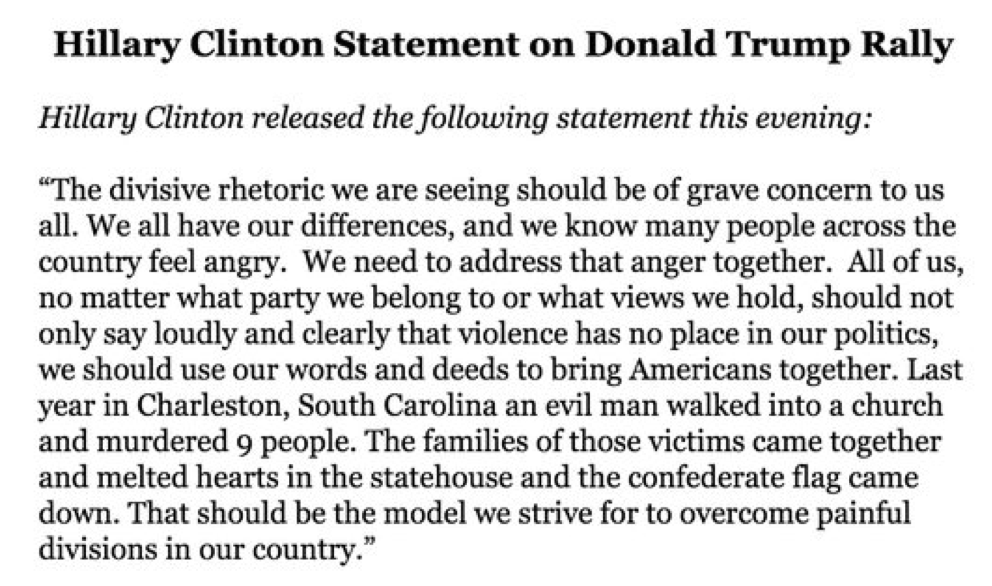

I suspect that this fundamentally oligarchical worldview is behind a lot of Clinton’s political missteps. When she brags about being praised by Henry Kissinger, she seems genuinely surprised that there are people who don’t find that to be a compelling reason to vote for her. And it helps to explain her response to the protests that led Donald Trump to cancel his rally in Chicago on Friday:

Her message seems to criticize the protesters as much as Trump’s rhetoric — a profoundly authoritarian stance that seems natural if you assume that politics should be a conversation among a very limited set of elites, and that all the little people just need to be more polite and deferential.

Fundamentally, to me, Hillary Clinton acts less like someone running for President, and more like someone applying for a job as Head Animal Control Officer. She has mustered the support of the town council, and she has a letter of recommendation from the Chief of Police. But she can’t for the life of her understand why all the dogs in the pound keep interrupting her, acting as if they should have a say in the decision.

Don’t get me wrong. I suspect that she would be a relatively benevolent dog catcher. Compare Donald Trump, who is campaigning on a promise that he will euthanize all the dogs and turn them into a plentiful supply of cat food.

Her second apology for her bizarre statements about Nancy Reagan was a huge improvement. It was as if, when sufficient pressure was placed on her, the hundreds of millions of people who are not part of the political, financial, and media elite came momentarily into focus for her. It was disappointing, however, that her ability to acknowledge the courage and importance of regular Americans did not even persist to the end of the statement.