Socrates and Plathiel continue their conversation, now discussing the best form of government.

In its native habitat: http://darwineatscake.com/comic/en/179

Socrates and Plathiel continue their conversation, now discussing the best form of government.

In its native habitat: http://darwineatscake.com/comic/en/179

After yesterday’s primary in Indiana, both Ted Cruz and John Kasich have dropped out of the race, leaving Donald Trump as the presumptive nominee for the Republican party. This was disappointing to those of us who were hoping for some contested-convention drama, but sensible, since Trump is now virtually certain to go into the convention with the 1237 pledged delegates required to secure the nomination on the first ballot.

At various points during this primary season, I’ve calculated what the delegate counts would have been under alternative allocation schemes. The Republican party uses a process that varies from state to state. In general, the early states tend to allocate delegates more proportionally among candidates, while later states tend to be more winner-take-all. By contrast, the Democratic party uses a uniform method: proportional allocation among the candidates receiving more than 15% of the vote (applied both at the state and congressional-district levels).

Under the actual scheme, Trump currently has about 1013 pledged delegates (plus, possibly, some supporters among the formally unpledged delegates from Pennsylvania). He only needs to win about half of the remaining 445 delegates to reach the threshold, and he would be almost certain to do so, even if Cruz and Kasich stayed in the race.

However, if the Republicans used the Democratic scheme (applied only at the state level, for simplicity), Trump would have 912 pledged delegates, and would need 73% of the remaining delegates to prevent a contested convention. Under proportional allocation with no threshold, he would have 799 delegates, and would need to win over 98% of the remaining delegates.

One consequence of (and perhaps rationale for) using winner-take-all allocation in a drawn-out primary season is that it drives out challengers, forcing consensus around the leading candidate and allowing them to begin their general-election pivot earlier.

Another consequence is that a pesky plurality of “voters” can drive the nomination of an openly bigoted narcissist, subverting the ability of the party elite to install one of the usual cryptically bigoted narcissists. That’s a consequence that will either be hilarious to Democrats in November or hilarious to extraterrestrial archaeologists who visit the smoldering remains of our planet thousands of years in the future.

Methodological notes:

Today, both the Republican and Democratic parties will be holding their primaries in New York. What should we expect from the Republican primary? Briefly, the most likely outcome is that Donald Trump will walk away with more than 80 of New York’s 95 delegates. The exact number will depend on the share of the vote that Trump gets, both statewide and in the various congressional districts. However, there are 27 congressional districts, which is a large enough number that we can predict the distribution of results, without worrying about the details of individual districts. That, along with New York’s delegate allocation rules, gives us the following curve:

538’s final polling average has Trump at 52.1%. We can adjust this based on the relationship between Trump’s polling numbers and his final performance, but the adjustment turns out to be pretty small. Best guess is for Trump to get 51.9% of the vote, which would give him about 84 delegates.

That’s the headline. If you’re interested in the details, keep reading.

The red line is the predicted relationship and the black dot is the specific prediction. The blue line is an alternative predicted relationship based on a lower variance among congressional districts (details below).

New York has a total of 95 delegates for the Republican primary. Fourteen of those are allocated based on the statewide results. The other 81 are allocated based on the results in the various congressional districts.

If one candidate gets more than 50% of the statewide vote, they get all 14 of the statewide delegates. If not, delegates are allocated proportionally among the candidates receiving at least 20% of the vote. That’s what creates the discontinuity in the graph above. If Trump gets over 50%, he’ll get all 14. If he gets just under 50% (and Cruz and Kasich both get over 20%), he’ll probably get seven of them.

That graph assumes that both Cruz and Kasich get at least 20%. In the unlikely and very specific scenario where, say, Cruz gets 19.9% and Trump gets 49.9%, Trump would get about 5/8, or about 9 of the statewide delegates. That’s not a big difference, but it is sort of interesting that, in New York, it might be that a strategic anti-Trump movement would want to split their votes between Cruz and Kasich to ensure that both get over the threshold. That runs counter to the conventional wisdom in most states, which says that anti-Trump voters should rally behind whichever non-Trump candidate is more viable.

Three delegates are allocated on the basis of the results in each of New York’s 27 congressional districts. Here are the rules that are relevant to the current election:

If one candidate receives more than 50% of the vote, they get all three delegates.

If not, the leading candidate gets two delegates, and the second-place candidate gets one.

Given Trump’s commanding lead in the polls, it seems likely that he will win most or all of the congressional districts. His delegate haul will depend primarily on the number of districts in which he gets over the 50% mark.

We can guess at this if we assume that the individual congressional districts are Normally distributed around a mean given by the statewide result. What we need, then, is a standard deviation for that distribution.

If we look at earlier Republican primary results, we find that the standard deviation among congressional districts clusters around two values. Most of the states for which results by congressional district are available have standard deviations of around 4, including Missouri, Mississippi, Texas, Tennessee, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Alabama. But Wisconsin and Georgia both had standard deviations of around 7. My instinct is that New York is more like Wisconsin and Georgia, and the curve shown above uses a standard deviation of 7.

If we use a lower standard deviation, like 4, we get the blue curve in the figure above. The upper part of the curve gets a bit steeper. If Trump gets over 50% statewide, reduced variance among congressional districts means that he falls below 50% in fewer of those districts.

The lower part of the curve is fairly insensitive to the standard deviation. If Trump is below 50% on average, higher variance means that he gets over 50% in more congressional districts. However, it also means that he is more likely to come in second in other congressional districts. On the whole, it’s a wash. The curves above assumes that Trump comes in second in any CD where he receives less than 37% of the vote.

Going into today’s Democratic primary in Wisconsin, the polls have Sanders with an edge of 2-3 percentage points over Clinton. The obvious expectation would thus be that Sanders will win by about two or three points. Except that the polls have been wrong this primary season. I’m not talking about Michigan, where polling missed the election outcome by 20 points — or not just about Michigan anyway.

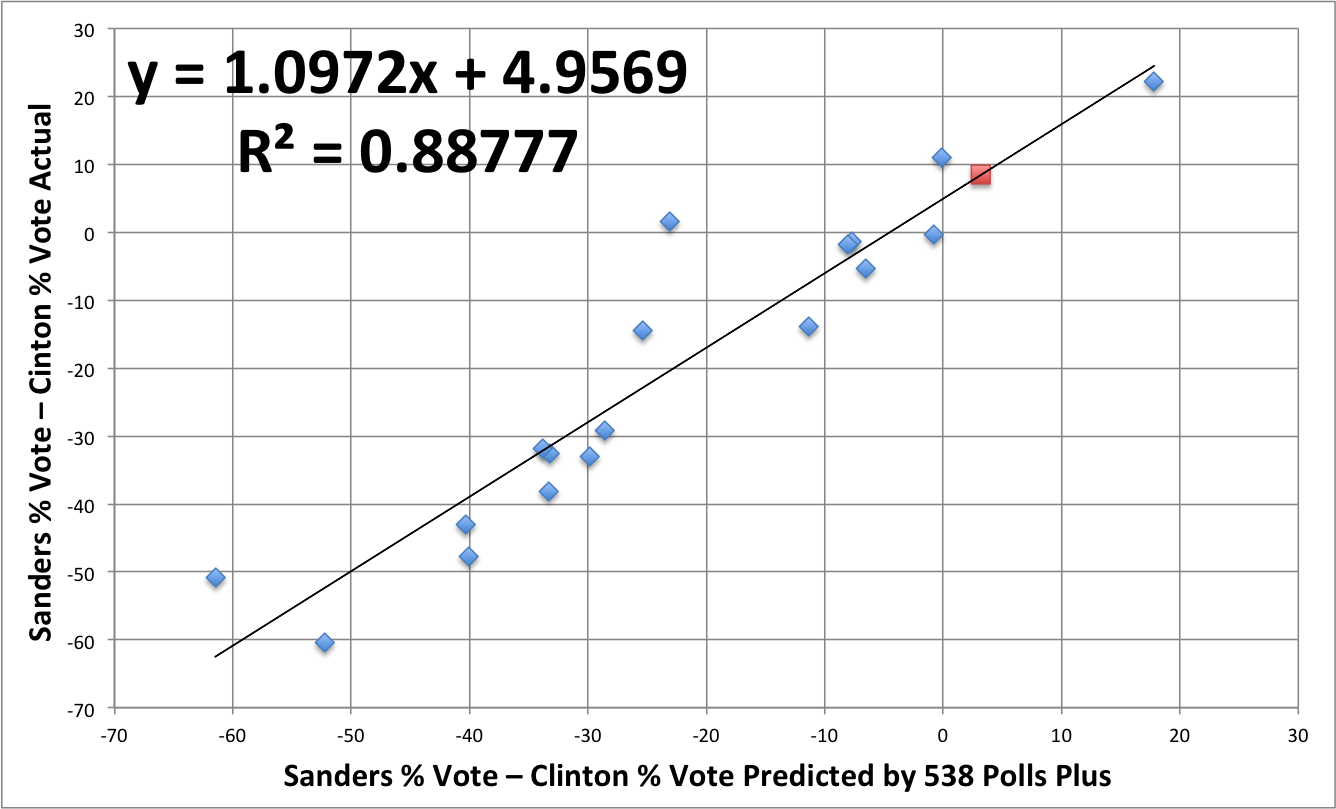

Previously, I did a simple linear regression on the primary results to date, comparing the final polling averages and projections to the actual outcome. I’ve updated that analysis with the more recent results, although the result is more or less the same:

When we compare the final polling averages to election outcomes, we find two things. First, the regression line has a slope greater than one: in the states where Clinton was expected to win big, she mostly outperformed expectations; in states where Sanders was favored, he tended to overperform. This sort of effect might come from a variety of places. For example, it could be that late-deciding voters tend to go with the candidate they think will win, or it could be that voters supporting a candidate very likely to lose become demoralized and stay home. Or, probably, lots of other things.

Second, there is an offset of about 5 points. That is, in close races, Sanders does about five points better on average than the final polling numbers would predict. I am fairly certain that this offset is due to a mismatch between the voter turnout models used by pollsters and the reality this election. Specifically, this election seems to have significantly higher turnout among younger voters compared with previous years. And those younger voters heavily favor Sanders. So, when a pollster constructs their final numbers using a model based on 2012 turnout, they underestimate the number of young Sanders supporters.

The final projection from 538’s Polling Plus model has Sanders winning 50.2% of the vote in Wisconsin to Clinton’s 47.2%. Plugging that into the regression formula gives a Sanders margin of victory of 8.3%.

In the Democratic primaries, delegate apportionment tends to track pretty close to the raw vote totals. So this would project Sanders to win about 46 of the state’s 86 pledged delegates.

In order to go into the national convention with half of the pledged delegates, Sanders needs to win a little over 56% of the remaining delegates. An eight-point win today would give him about 54% of today’s delegates, which would leave the race in pretty much the same state it has been in for a while: Sanders has a shot at overtaking Clinton, but you would not get anything close to even odds on it.

One methodological note: the regression presented here does not include any of the results from the last two rounds of primaries and caucuses — most of which Sanders won by large margins — because there was little to no polling data for those states in the run-up to their elections.

One final note: the conventional what-passes-in-political-punditry-as-wisdom is that Sanders does best in caucus states, while Clinton does better in primaries. That may be true, but all of the points included here are from primary states, with the exception of Nevada. (If we exclude Nevada, the projection changes only slightly: to Sanders by 8.8%.) So, even if there is a primary versus caucus effect, the fact that caucus states received so little polling means that is does not have much effect on this analysis.

Ever since Donald Trump established himself as the clear frontrunner in the Republican primary, there has been a lot of talk, particularly from the anti-Trump Republican establishment, about the possibility of a brokered convention. It has been clear for some time that Trump would almost certainly wind up with the largest number of pledged delegates. However, if he has fewer than 50% of the delegates going in to the convention, he won’t win the nomination on the first ballot, and the voting rules make it possible for the Republicans to consolidate anti-Trump support around someone else. This could be Cruz or Kasich, or it could be someone else entirely, like Mitt Romney’s suggestion: Mitt Romney!

But is that possible? Under the Republican delegate allocation schemes in the upcoming primaries, almost certainly not. In fact, if he wins only 40% of the vote in each state, but continues to beat Cruz and Kasich, he will coast to the nomination easily.

Yesterday I posted an updated calculation comparing the current Republican delegate counts to what those counts would be if the Republicans used a more proportional delegate allocation scheme. Here’s that table, again. (Details, notes, and caveats can be found in the original post.)

There’s not a qualitative difference in the delegate totals, or in the apparent state of the race. Trump is the clear frontrunner, with a sizeable lead over Cruz. But, in terms of the possibility of a brokered convention, the difference is huge.

In all of the Democratic primaries, delegates are allocated proportionally among all of the candidates who receive more than 15% of the vote (some statewide, and some by congressional district). If the Republicans had used this scheme in all of the primaries and caucuses to date, Trump would currently have about 613 delegates, and he would need to win 624 of the approximately 1000 delegates remaining in order to capture the nomination on the first ballot. Under proportional allocation, that would require him to receive more than 60% of the vote from here on out.

That’s not impossible, of course, but it’s pretty close. Trump has earned more than 50% of the vote in only one contest to date: the Northern Mariana Islands. And even after Rubio’s withdrawl from the race, he is still polling below 50% nationally among Republicans. So, under a proportional-allocation scheme, Trump would probably be expected to wind up with about 1100 delegates, well short of the 1237 he needs. The party would then be in a position to select a different nominee. Whether or not they would do it, I don’t know, but they would have the option.

But, that’s not the scheme they have. The Republican process involves a variety of delegate-allocation schemes, but, on average, they are more winner-take-all than the Democratic scheme. As the race stands, Trump needs only 545 of the remaining delegates to claim the nomination on the first round. And, if he is able claim a plurality of the vote in most of the remaining contests (as the polling suggests he will), he will easily exceed that number.

Here’s a breakdown of how the remaining Republican delegates are going to be allocated:

Six states award all of their delegates to the state-wide winner: Arizona 58, Delaware 16, Montana 27, Nebraska 36, New Jersey 51, and South Dakota 29, for a total of 217.

Six states award a fraction of their delegates to the state-wide winner: California 10, Indiana 30, Maryland 14, Pennsylvania 17, West Virginia 22, and Wisconsin 18, for a total of 111.

Six states award a fraction of their delegates in a winner-take-all manner, but broken down by congressional district (3 delegates per CD): California 159, Connecticut 15, Indiana 27, Maryland 24, West Virginia 9, and Wisconsin 24.

Oregon and Utah allocate proportional to the statewide vote (28 and 40 delegates, respectively), with a winner-take-all trigger at 50% in Utah.

Five states award a fraction of their delegates proportional to the statewide vote: Connecticut 13, New Mexico 24, New York 14, Rhode Island 13, and Washington 14, for a total of 78.

Three states use proportional allocation within individual congressional districts: New York 81, Rhode Island 6, and Washington 30, for a total of 117.

Finally, there are 88 weird delegates, who will go to the convention formally unpledged. 6 delegates from American Samoa and 28 from North Dakota will be chosen by party caucuses, but not rely on a popular vote. In Pennsylvania, 54 delegates will be elected from the 18 congressional districts. They will have announced whom they intend to support, but will not be bound.

So what happens if Trump gets only 40% of the vote in each state, but continues to beat Cruz and Kasich? Well, he wins 328 delegates from the state-wide winner-take-all allocations. He probably also wins the vast majority of the congressional-district winner-take-all delegates, but if we conservatively give him only half of those, that’s another 129 delegates. If we give him 40% of the proportional-allocation delegates, that’s another 105.

That’s a low-ball estimate of 562 right there. And that’s not including any Pennsylvania delegates, who, if they’ve indicated their support for Trump, are probably actual Trump supporters, and would vote for him at the convention, even if they don’t have to.

More realistically, 40% statewide probably earns him at least 70% of the winner-take-all by congressional district delegates, as well as 70% of the 54 unpledged Pennsylvania delegates.

That’s 651, more than 100 delegates in excess of what he’ll need to claim the nomination on the first ballot.

So, bleeding away delegates from Trump at the margins is no longer a viable anti-Trump strategy. If the Republicans want a brokered convention, they’ll need for one of the other candidates to actually beat him, probably in at least three or four of the remaining states. Given that most of the remaining states do not have large evangelical populations, and are not Ohio, that could be a real challenge.

Previously, I did a calculation to compare the state of the Republican primary with what things would look like under a scheme where delegates were allocated strictly proportional to the popular vote. Here, I’ve updated that calculation to reflect estimated delegate totals through the March 15 primaries.

I’ve also added a new calculation, which is proportional allocation among all candidates who receive more than 15% of the vote. This is similar to what the Democrats do, except that the Democrats allocate some delegates based on the statewide vote, and some based on the voting in each congressional district. For simplicity, I’ve done the calculation here only at the statewide level.

The Republican primaries use a variety of allocation schemes, from proportional allocation with no threshold (North Carolina) to winner-take-all (Florida and Ohio), with various hybrids. Overall, relative to the Democratic scheme, Republican contests tend to be more winner-take-all, and that will be increasingly true for the later primaries.

There are about 1000 delegates left, of which Trump needs about 545 to win the nomination on the first ballot. With a number of additional winner-take-all states coming up, this seems the most likely outcome. Under even the thresholded proportional scheme, he would need 624, which, under that scheme, would be a tall order, given that he has received less than 50% of the vote in every contest so far, with the exception of the Northern Mariana Islands.

Notes:

Not all of the results from Tuesday have been finalized. Here I have used the current estimates from The Green Papers. In particular, I’ve assigned Missouri’s delegates 37 to Trump, 15 to Cruz, and for Illinois, I’ve given 54 to Trump, 9 to Cruz, and 6 to Kasich. The numbers in Ohio, in particular, might change quite a bit.

I have not included the delegate counts from the three jurisdictions from which raw vote totals are not available. Wyoming has a weird caucus system that is still in progress. At the moment, they’ve got nine delegates pledged to Cruz, and one each to Trump, Rubio, and Uncommitted. There are 14 more delegates whose pledges will be determined at later rounds of their caucus system. I have also not included delegates from Guam or the Virgin Islands, each of which has nine delegates. As I understand it, the Virgin Islands is sending six as pledged uncommitted, and three unpledged (with a stated preference for uncommitted). Guam’s delegates are all unpledged. One has stated a preference for Cruz, five for uncommitted, and three yet to be determined. So, of the 44 total delegates not included in my totals, 27 have been determined, 26 of which could possibly be counted as “anti-Trump”.

That is, if you’re a Bernie supporter.

If you’re a Hillary supporter, you should vote for her. What you should NOT do is stay home because the nomination is a foregone conclusion (no matter which candidate you support). Nor should you vote for Clinton out of a sense that getting your vote in the primary will somehow help her in the general election.

After each primary where Clinton did well, there has been a rush to declare the primary over, naming her as the inevitable nominee. Partly this is driven by exaggerating her delegate lead by lumping together pledged and superdelegates. I’m not making the argument that the superdelegates are not legitimate; the process is what it is. But, I find it hard to imagine that, in a two-candidate race where neither of the candidates is a raging Trumpian psychopath, the bulk of the superdelegates would not throw their support behind the candidate with the most pledged delegates (see, e.g., 2008). But it is unsurprising that, following Clinton’s performance in Tuesday’s primaries, the Sanders campaign has once again been pronounced dead, with even President Obama seeming to get in on the act.

So, if you’re a Sanders supporter, is it still worth it to go out and vote for him? What if you prefer Sanders to Clinton, but very strongly prefer Clinton to either Trump or Cruz? Yes and yes, and it is worth encouraging everyone you know (Clinton and Sanders supporters alike) to go out and vote as well.

Here’s why:

It is true that, after Tuesday, Sanders faces an uphill battle in a way that is qualitatively different than before Tuesday. Delegate counts are not fully finalized from Tuesday, but it will be something close to 398 for Clinton and 293 for Sanders, bringing their totals to 1173 and 845, respectively (by my records). In order to come into the convention with more than half of the total pledged delegates, Sanders would have to win over 58% of the remaining delegates.

It is probably true that the remainder of the map favors Sanders, and that he tends to outperform the polls by a few percentage points in close contests. However, it is also true that he has been stuck about 10% behind Clinton in the national polls. So, with things continuing as they are, Sanders might well capture half of the remaining delegates. To overtake Clinton, he probably needs a ten-point swing nationally. And, if the swing does not start soon, it will need to be even bigger.

A ten-point swing is not likely, but neither is it impossible. And if it were to happen, it sure would be dumb if Sanders voters stayed home.

In races with three or more candidates, it makes sense to think about your vote strategically. With only two, there is no reason to do anything other than vote for the candidate you prefer. If Clinton is on track to win, there is no mechanism through which voting for Sanders makes him into a Nader-esque spoiler, and Jim Webb gets the nomination.

In fact, I think that having the primary continue to be actively contested over the next few months would actually benefit Clinton in the long run. If this were a particularly divisive primary, it might be different, but this year’s Democratic primary has actually been the most congenial presidential primary I’ve ever seen (excepting most of the ones involving a sitting President). Just think of this year’s debates. Both Clinton and Sanders get a little shouty at times, but 90% of the time they’re shouting agreement at each other.

You may have seen this graph from the New York Times. The main point was to show how much free airtime Trump has gotten by making himself entertaining and newsworthy. But the other thing to notice is just how the free media dwarfs bought media for all of the candidates. If the primary goes quiet, the news has much less reason to cover Clinton. An active primary means an ongoing national platform for the Democratic party and their policy positions.

Part of the argument is that, now that Clinton is likely to be the nominee, people need to start unifying around her. This is an anxiety that gets thrown around every primary, and (almost) every time, everybody comes together just fine in the few months leading up to the general election.

It is true that there are Sanders supporters out there who are feeling frustrated and disenfranchised at the moment, and some of them are claiming that they will stay home in November, or even vote for Trump. This is typically met with outrage from Clinton supporters claiming that the Sanders supporters have a moral obligation to back Clinton. Three things:

First, actually, no. The thing about democracy is, each of us gets to decide whom to vote for. We are each allowed to vote “against our own interests”, or in ways that don’t make sense to other people. There are some people who genuinely believe that the corruption of the system is so bad, and that Clinton is so bought in to the system, that they can not in good conscience support her. This is allowed.

Second, the vast majority of angry, disappointed Sanders supporters will probably wind up backing Clinton if she becomes the nominee, just as most of the Clinton supporters who said they would never vote for Obama in 2008 came around. Even among those who feel that Clinton is irredeemably corrupt, I suspect there are very few who would actually prefer a Trump presidency.

Third, people get that Sanders is a long shot. He always has been. If he does not win the nomination, his supporters are going to get over it. But the movement is fueled by people who feel that the political establishment does not listen to or represent them. Preemptive calls for Sanders to quit the race simply reinforce that feeling.

Presidential races are what bring people to the polls, but the elections for the House and Senate, and all the state and local level positions are just as important. For most aspects of daily life, they’re probably much more important. So go and vote in the primary, no matter what the delegate count is. But also spend some time to figure out which of the candidates in the other races on the ballot most closely reflect your values, and vote for them.

We’ve already seen two important results, in Chicago and Cleveland. In the Chicago primary, Cook County State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez lost to Kim Foxx as a result of her reluctance to prosecute Police Officer Jason Van Dyke for the shooting of Laquan McDonald. In Cleveland, the primary ousted Cuyahoga County prosecutor Tim McGinty after he failed to indict Timothy Loehmann for shooting Tamir Rice.

When Sanders started his campaign, no one (including, I think, him) thought he had a shot at the nomination. The hope was that he would be able to raise certain issues, and generally pull the conversation to the left, maybe leading to a more progressive party platform.

And, it has worked! Hillary Clinton has sounded a lot more progressive over the course of the primary. But I would be willing to place a fairly large bet that as soon as she is fully confident of her victory, she will begin the archetypally Clintonian process of triangulation. She will immediately start tacking back towards more conservative positions in anticipation of the general election. The longer Sanders supporters can keep the primary competitive, the more progressive of a candidate, and hopefully President, Clinton will be.

And that’s important not only for people pulling for a more progressive Democratic party, but for anyone who wants to see a Democrat elected President in the fall, because . . .

The conventional wisdom used to be that a successful presidential candidate needs to pander to the base in the primary, and then pivot back to the center in the general election. However, as the electorate has become more polarized, and the two parties have become more ideologically homogeneous, things have changed. There are far fewer people now who decide on a case-by-case basis whether to vote for the Democrat or the Republican. Elections are won by the party that does a better job of inspiring their supporters to actually show up at the polls.

One of the remarkable things about the Sanders campaign has been its success with young people — a demographic that typically has very low voter turnout. The eventual nominee will need that group to show up in November, because while many Republicans are uncomfortable with Trump, his base is very, very motivated.

This is the thing that worries and frustrates me the most about the “inevitability” argument. A corollary of the argument that Clinton has already won is that if you’re in a state that has not held its primary yet, your vote does not matter. There were times during this campaign when it felt like “suppress turnout for Sanders through demoralization” was an explicit part of the Clinton campaign strategy.

There’s a sense in which most of our individual votes don’t matter, of course, in this or any other election. However, collectively, our votes matter a lot. And we only show up if we feel like our vote means something.

This is one of the really nice things about the proportional delegate allocation scheme in the Democratic primaries. Even if your candidate is sure to win (or sure to lose) your state, your vote is still important, because the margin of victory matters. (It would matter even more if the idiocracy of the political media quit reporting all primary results as if they were winner-take-all contests.)

And getting people to show up and vote in the primaries — even if they don’t vote for your preferred candidate — is important because . . .

The fact is, if you get registered and actually vote in the primary, you’re a lot more likely to show up at the polls in November, and in November two and four years from now. Even if we accept Clinton’s nomination as a foregone conclusion, the best possible thing would be for Sanders to continue to hold rallies and give speeches right up to the convention. Some of the first-time voters who get excited by him may lose interest if he does not win the nomination. But for many of them, enthusiasm for Sanders may be what gets them politically engaged. And that’s fantastic, no matter which candidate you support.

Sanders’s success so far has been so remarkable partly because his campaign violated several of the deeply ingrained tenets of received political wisdom, like that you have to be willing to cozy up to big-money individuals and groups to finance a campaign. The most surprising thing, though, was his success at running as an unabashed progressive, even embracing the word “Socialist”.

[As an aside, if you think that Sanders was always a non-starter in America because he is a “Socialist”, you either don’t understand his positions, or you don’t know what “Socialist” means. His positions are “Socialist” in the sense that he would probably be a center-right candidate in Scandinavia. He has been described as a “New-Deal Democrat”, although I would have said that he is actually maybe more like an Eisenhower-era Republican.

However, if you think that Sanders was always a non-starter in America because, after decades of right-wing propaganda and the systematic undermining of the public education system, most Americans have an ignorant and irrational fear of the word “Socialism”, you may be on to something. Although, his success among younger voters suggests that this is becoming a less and less valid argument.]

The message is that there are millions and millions of Americans who are desperately enthusiastic about ideas like universal health care, a more progressive tax code, aggressive Wall Street regulation, and free college (again, all mainstream ideas in most wealthy Western democracies). Who is the message for? I suspect it will not find much of an audience with politicians who are well entrenched the system. But hopefully it will inspire future candidates to champion these sorts of policies.

And this, to me, is the strongest argument for trying to send Sanders to the convention with as many delegates as possible. Even if he does not win the nomination, the larger his delegate count, the more it will embolden other Democrats to embrace the sorts of policy positions that he has built his campaign around.

And that is the path forward that leads to a future Bernie Sanders, one who does have the backing of the party establishment.

Today, March 15, the Democratic primary will be allocating 691 delegates based on voting in Florida, Ohio, Illinois, Missouri, and North Carolina. Yesterday, I posted a rough calculation suggesting that Sanders would need to win about 351 of those delegates in order to be on track to win half of the pledged delegates before the convention.

[NB: If he wins more than that, it by no means guarantees that he will win the nomination. Similarly, if he wins fewer, it does not guarantee that Clinton will win. Which is to say, whomever you support, go vote! Also — maybe even more importantly — figure out who sucks the least in your local down-ballot races, and vote for them!]

So what is actually going to happen today? Well, if we look at the polling averages at aggregators like Real Clear Politics or 538, they suggest that Clinton will carry all five states, with big wins in Florida and North Carolina, and narrower margins in Ohio, Illinois, and Missouri. But is taking the polls at face value the best approach? (Spoiler: No)

We’ve now had enough primaries that we can reasonably compare polling averages and actual outcomes. The following three graphs plot the advantage held by Clinton in the final polling averages or projections before each primary versus Clinton’s actual margin of victory. So, Sanders victories show up as negative numbers. These plots do not include states like Colorado and Minnesota, where there was very little polling before the primaries, and also leaves out Vermont and Mississippi — because you start to get non-linear behavior in landslides.

First, for Real Clear Politics’s polling averages:

The red line is a linear regression, and the blue line is what you would expect if polling were accurate. Michigan is a big outlier, but the rest of the results lie reasonably close to the line (overall R2 = 0.84).

Looking at the blue curve, it seems clear that the polls systematically underestimate the margins of Clinton’s victories in the states where she wins big, and they underestimate Sanders’s performance in states where the competition is close.

The slope of the red line is 1.46, and the intercept is –6.58. One interpretation of the >1 slope would be that undecideds tend to go with the winner, because they shake out proportional to the rest of the voters and/or due to a bandwagon effect. The negative intercept, on the other hand, suggests a systematic underestimation of Sanders’s support. Given the very pronounced difference in the typical ages of Sanders and Clinton supporters, and the high turnout of young voters in this primary, I’m inclined to think that this reflects a mismatch between polling firms’ likely voter models and reality.

Whatever the reasons, the red line does give us a way to estimate likely outcomes based on the polling data. Here’s what that looks like:

Here, again, the values indicate Clinton’s expected margin of victory. This regression would predict narrow wins for Sanders in Missouri and Illinois, a narrow win for Clinton in Ohio, and huge wins for Clinton in Florida and North Carolina. This outcome would give Clinton about 399 delegates and Sanders 292.

We can do the same thing for 538’s polling averages. The difference is that RCP uses a simple average of some number of the most recent polls, while 538 uses a continuous weighting scheme to account for poll recency as well as weights reflecting sample size and performance history of individual polling firms. The result is qualitatively similar, however:

Here the slope is 1.4, offset –6.33, and R2 = 0.89. This predicts results of

Compared with the RCP analysis, this predicts a smaller margin for Clinton in North Carolina, but predicts that she will win Illinois. The predicted overall delegate haul is nearly identical, though: Clinton 403, Sanders 288.

Finally, we can look at 538’s “Polls Plus” estimator, which includes information about things like endorsements:

Here, the slope is much lower, 1.24, indicating that this method has done a better job of predicting the magnitude of Clinton’s previous wins. The offset is similar, at –6.44, and the fit is the best of the three, with R2 = 0.91. Predicted results:

Projected delegate count: Clinton 401, Sanders 290.

This would, of course, fall quite short of Sanders’s target of 351.

So, in order not to lose even more ground to Clinton, Sanders would need to a substantial swing. Is that possible? The results in Michigan clearly indicate that it’s possible, although the results from all of the other states suggest that it’s not very likely.

There are a couple of places a substantial deviation could come from. First, if actual voter prefernce has been changing rapidly over the past week, the polling averages will naturally lag behind that change. Even individual polls are typically conducted over the course of a few days. So, if Clinton’s recent statements about Nancy Reagan, or the Chicago protests, or the Death Penalty, or Libya have alienated any Democrats, that may not be fully reflected in the polls.

Second, in states with open primaries, Democratic voters may cross over, particularly in light of the increasingly urgent anti-Trump movement. If those crossover voters are substantially more likely to be Clinton supporters than Sanders supporters, that would create a shift. A friend in Michigan told me, anecdotally, that she knows a number of Clinton supporters who did just this, partially due to the polls, which indicated that Clinton would win the state easily.

Adding a ten-point swing (e.g., due to 5% of voters switching from Clinton to Sanders) to the 538 Polling-Plus projections would give Sanders victories in Ohio, Illinois, and Missouri, and would produce a delegate count of Clinton 366, Sanders 325. This, incidentally, would be very close to 538’s uncorrected delegate targets.

Sanders would need a swing of about 17.5 points in order to reach the delegate target of 351, which accounts for Clinton’s current lead.

Of course, even if there is a swing, it is unlikely to be uniform across the states. Which means that it is finally time for tea-leaf reading!

I wanted to get down my own predictions, which are going to start from the 538 Polling Plus correction described above, but then use some intuition based on eyeballing the polls for trends and outliers. Here goes:

Florida: Clinton +30, Delegates: Clinton 139, Sanders 75

There’s a modest trend in the past few days that is not captured in 538’s average, but it may not have much effect, due to high rates of early voting in Florida.

Ohio: Sanders +1, Delegates: Sanders 72, Clinton 71

There’s again a sharp recent movement toward Sanders, and, if crossover votes do take away preferentially from Clinton, this is the state where we should see the biggest effect.

Illinois: Sanders +5, Delegates: Sanders 82, Clinton 74

Here, there are polls from March 7 and earlier, which all have Clinton leading by 20 to 40 points. Four polls with more recent data give Clinton an average lead of +2, and the three that are entirely from the last week give Clinton an average lead of less than 1 point.

Missouri: Sanders +8, Delegates: Sanders 38, Clinton 33

Very little polling data here, but, again, evidence of a recent shift towards Sanders.

North Carolina: Clinton +22, Delegates: Clinton 65, Sanders 42

Maybe a recent shift, but probably not more than a point or two.

Total: Clinton 382, Sanders 309

This would put Sanders still short of his targets, but, if he can actually claim victory in Ohio, Illinois, and Missouri, that will probably be enough to maintain his plausibility as a candidate. And so we will reconvene for the next round of primaries!

On Friday, while attending Nancy Reagan’s funeral, Hillary Clinton gave an interview to MSNBC in which she made the following statement:

It may be hard for your viewers to remember how difficult it was for people to talk about HIV/AIDS in the 1980s. And because of both President and Mrs. Reagan, in particular, Mrs. Reagan, we started national conversation when before no one would talk about it, no one wanted to do anything about it, and that too is something that really appreciated, with her very effective, low-key advocacy, but it penetrated the public conscience and people began to say ‘Hey, we have to do something about this too.’

This was a very strange and dumb thing to say, even for someone who seems to make as many unforced errors as Clinton does. As social media and news outlets quickly reminded her, the truth of the matter was much closer to the opposite of what she said. The Reagan administration, including Nancy, was legendarily silent on the issue.

The Clinton campaign’s initial apology seemed almost as bad:

“Misspoke” seemed like a bizarre and dismissive characterization of a full-paragraph of revisionist hagiography that was clearly part of her prepared remarks for the interview, and this terse apology did not do much to stem the criticism.

However, on Saturday, Clinton posted a much longer apology that explicitly denied the credit she had given to the Reagans. And, importantly, she explicitly gave credit to the many, many activists who did start our national conversation about AIDS in spite of the depraved indifference of the Reagan administration.

To be clear, the Reagans did not start a national conversation about HIV and AIDS. That distinction belongs to generations of brave lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people, along with straight allies, who started not just a conversation but a movement that continues to this day.

The AIDS crisis in America began as a quiet, deadly epidemic. Because of discrimination and disregard, it remained that way for far too long. When many in positions of power turned a blind eye, it was groups like ACT UP, Gay Men’s Health Crisis and others that came forward to shatter the silence — because as they reminded us again and again, Silence = Death. They organized and marched, held die-ins on the steps of city halls and vigils in the streets.

One can quibble, of course. While walking back her praise of the Reagans, it ignores the gut-churning cruelty that characterized much of the administration’s response. And there’s the fact that much of the rest of her statement is basically about how she, Hillary Clinton, is the actual hero of the story. But, it was a political funeral in the middle of an election, so those omissions and that spin are not surprising. And, as far as apologies from politicians go, this was was really pretty good.

So, my anger has subsided somewhat, but I have continued to be puzzled as to why she possibly made this statement in the first place. The theory that makes the most sense to me, as bizarre as it is, is that this was actually Hillary Clinton’s perception of the events of the 1980s.

Garance Franke-Ruta (storified here) makes this argument:

(And a bunch more interesting points. Well worth reading, and clicking through the links.)

There was also this article, published in the Advocate on March 6, shortly after Nancy Reagan’s death, and several days before Clinton’s comments. The article presents the Reagans’ relationship with AIDS in the most generous possible light, with several passages of this flavor:

Nancy Reagan is sometimes credited with pushing her husband to do something about AIDS, and he eventually supported some funding for research. The death of their friend, actor Rock Hudson, is often referred to as a pivotal moment.

So there is a very specific perspective from which Clinton’s original statement can be seen as, well, sort of true. It’s sort of a Great Man Theory perspective. Sure, there were lots of things happening, people saying things, protesting, and so on, but the important part of the history is what happened within the walls of power. If by “national conversation” you mean “conversation among the nation’s elite”, and if by “the public conscience” you mean “the public consciousness”, and by “the public consciousness” you mean “the consciousness of the political establishment”, maybe Nancy Reagan was a key driving force.

I suspect that this fundamentally oligarchical worldview is behind a lot of Clinton’s political missteps. When she brags about being praised by Henry Kissinger, she seems genuinely surprised that there are people who don’t find that to be a compelling reason to vote for her. And it helps to explain her response to the protests that led Donald Trump to cancel his rally in Chicago on Friday:

Her message seems to criticize the protesters as much as Trump’s rhetoric — a profoundly authoritarian stance that seems natural if you assume that politics should be a conversation among a very limited set of elites, and that all the little people just need to be more polite and deferential.

Fundamentally, to me, Hillary Clinton acts less like someone running for President, and more like someone applying for a job as Head Animal Control Officer. She has mustered the support of the town council, and she has a letter of recommendation from the Chief of Police. But she can’t for the life of her understand why all the dogs in the pound keep interrupting her, acting as if they should have a say in the decision.

Don’t get me wrong. I suspect that she would be a relatively benevolent dog catcher. Compare Donald Trump, who is campaigning on a promise that he will euthanize all the dogs and turn them into a plentiful supply of cat food.

Her second apology for her bizarre statements about Nancy Reagan was a huge improvement. It was as if, when sufficient pressure was placed on her, the hundreds of millions of people who are not part of the political, financial, and media elite came momentarily into focus for her. It was disappointing, however, that her ability to acknowledge the courage and importance of regular Americans did not even persist to the end of the statement.

In the Republican presidential primary system, different states apportion their delegates among the candidates in a variety of ways. In the upcoming contests in Florida and Ohio, all of the state’s delegates are pledged to the candidate who receives the most votes state-wide. In Nevada, delegates are allocated proportional to the vote total (you get one of the 30 delegates for each 3.33% of the vote you get).

But a lot of the states are much more complicated. In South Carolina, three delegates are assigned to the leading vote-getter in each of the seven congressional districts, and the remaining 29 go to the winner statewide. Trump won all 50 this year by leading the pack in each congressional district.

A number of the states impose a minimum threshold. For example, Massachusetts and Kentucky do proportional allocation of their 42 and 46 delegates, respectively, among all candidates receiving at least 5% of the state-wide vote.

Several states add a winner-take-all threshold. Vermont does proportional allocation of its delegates among candidates who receive at least 20% of the state-wide vote. But if any candidate gets more than 50%, they receive all 16.

In general, the effect of these rules is to push delegates towards the winning candidates — and drive inviable candidates out of the race. This happens gently at first, as many of the early contests are more proportional. Then, as the season progresses, things take on more of a winner-take-all flavor.

Here’s what the allocation bias looks like in the Republican primaries and caucuses that have taken place through March 8 (data from The Green Papers):

The brownish-orangish line is what you expect from strictly proportional allocation of delegates, and the points plotted indicate allocations from individual state-wide (and Puerto Rico-wide) contests. Red is Trump, Blue is Cruz, Purple is Rubio, and Black is Kasich.

One thing you can see from the plot is that Trump seems to be the greatest beneficiary of the current allocation system. This makes sense, of course, since he’s the frontrunner, and the system is basically designed to drive a consensus around the frontrunner. And, if the frontrunner were anyone other than Donald Trump, the Republican leadership would probably be very pleased with how it was working.

As a little thought experiment, here’s what the current delegate score would look like if all of the Republican primaries and caucuses used proportional allocation without a viability threshold (besides whatever minimum percentage is required to get one delegate):

That’s not to say that things would have worked out this way under that allocation scheme, since a different scheme would have led to different reporting, different campaign strategies, and so on. But, it’s a nice simple way to quantify the effect of structural properties of the primary system on the outcome.

In that spirit, what this tells us is that about a fifth of Trump’s delegate total — and about half his lead over Cruz — can be chalked up to Republican delegate allocation math.

We could ask the same question for the Democrats, but it is not nearly as interesting. All of the Democratic contests follow the same formula: proportional allocation of delegates among candidates exceeding 15% of the vote. About a third of the delegates come from applying this formula to the state-wide vote, and about two thirds from applying it individually to each congressional district.

That system also punishes low-performing candidates, but it does not reward high-performing ones in the same way. There are no winner-take-all states or triggers (unless you win more than 85% of the vote, guaranteeing that no one else reaches 15%).

So, the Democratic system leans a bit more towards proportional overall. But much more important is the fact that there are only two competitive candidates, both of whom are rarely in danger of failing to meet that 15% threshold.

Red points represent Clinton, and Blue represent Sanders. The only real outliers are Vermont, where Sanders got 86% of the vote, and Mississippi, where Clinton topped 85% in two of the state’s four congressional districts.

I’m not advocating for any particular delegate allocation scheme here. We know there’s no perfect voting system. I just hope to contribute in my own small way to the enormous pile of regrets plaguing Republican party leaders as Trump sits atop his throne of skulls forcing them to fight to the death.