So, I just discovered the blog of Miles Corak, an Economics Professor at the University of Ottawa (via this short piece in The Atlantic Wire). He has been doing a series of posts about wealth and income inequality that are really interesting and accessibly written. At this time, there are five posts in the series (here, here, here, here, and here).

If you’re interested in a thoughtful, nuanced, and readable discussion of the economic factors underlying the Occupy Wall Street protests, check it out.

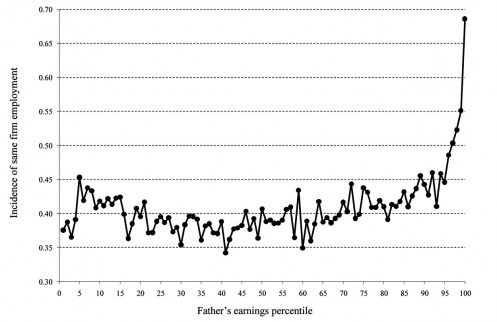

The most striking image comes from the post on nepotism, where Corak presents a graph from one of his own papers from the Journal of Labor Economics (accessible version available here) that shows the fraction of sons who work in the same firm as their fathers, as a function of income percentile. (Data for Canada)

Corak notes:

Connections matter. And for the top earners this might even be nepotism. This is not a bad thing if parents pass on real skills to their children, skills that might even be specific to particular occupations, industries, or even firms. If this is the case then it makes economic sense to follow in your father’s footsteps.

Wayne Gretzky often talked about the role his father played in developing his skating and stick handling skills. He spent hours and hours with Walter on the backyard rink. But not all top earners got to where they are because of this sort of good nepotism. I somehow doubt that James Murdoch is the Wayne Gretzky of the publishing world.

Bad nepotism promotes people above their abilities by virtue of connections, and it erodes rather than enhances economic productivity.

But there is even a larger cost. If the rich leverage economic power to gain political power they can also skew broader public policy choices—from the tax system to the education system—to the benefit of their offspring. This will surely start eroding the belief that labour markets are fair, and that anyone can aspire to the top.

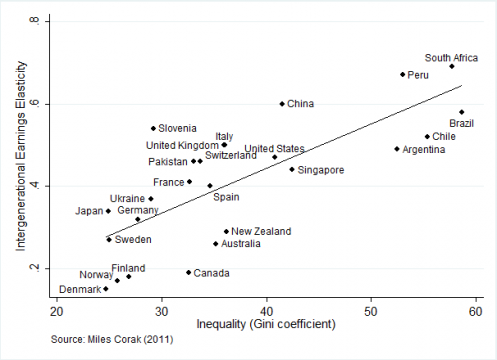

He also notes that the United States is among the most unequal of the world’s rich countries, as well as one of the most elastic. Elasticity, in this context, is the extent to which a person’s income is determined by the income of their parents.

Corak goes on to write:

These facts are finally starting to percolate into the American consciousness. Joseph Schumpeter, the Harvard University economist who taught during the 1930s, is often cited as saying that recessions are like cold showers: they clear the economy of inefficiencies, make the existing structures more apparent, and set the conditions for change.

But recessions have social as well as economic consequences. The current recession has shaken some people awake, and Occupiers signal the decline of the American Dream in our consciousness, a manifestation of underlying realities, and the demand for a change in the way of doing business.

Here’s hoping that there will be many more installments coming in this series.

Corak, M., & Piraino, P. (2011). Intergenerational Transmission of Employers Journal of Labor Economics, 29 (1), 37-68 : 10.1086/656371