Category Archives: Books

Prince Caspian on Wall Street’s arcane financial instruments

So, over the past two and a half years, a lot of opinions have been aired on the arcane financial instruments that were created, packaged, repackaged, sold, and leveraged by Wall Street Czars and Moguls. Some people view this activity as a natural extension of free-market capitalism, just as some people undoubtedly view eating children as a good source of protein. Other people view this self-referential and self-reinforcing “fake economy” as a financial cancer that nearly collapsed the world economy, just as some people view cancer as a cancer that kills people.

I’m still making up my mind.

While we have heard a lot on the topic from economists and politicians, one person we have not heard from is the fictional ruler of the fictional country of Narnia. Unfortunately, there are no surviving records from which we can reconstruct what Caspian X (the ruler formerly known as Prince Caspian) on these matters. However, we can infer a little something from Caspian’s questioning Governor Gumpas of the Lone Islands about islands’ slave trade.

Just to set the scene, we’re in Book 3 here, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. The Lone Islands are a part of the Kingdom of Narnia, but it has been about a hundred and fifty years since the last contact. So, the islands have been more or less self governing for a while. Caspian and the gang arrive to find a thriving slave trade, and Caspian insists that Gumpas abolish the practice.

The arguments that Gumpas puts forth to defend the slave trade could have come out of mouths of any one of the very serious people who have cautioned us against the chilling effect of imposing regulations, or curbing executive pay, or insisting upon transparency in how tax-supported funds are distributed among the elite.

“Necessary, unavoidable, a necessary part of the economic development of the islands, I assure you. Our present burst of prosperity depends on it.”

“Your Majesty’s tender years hardly make it possible that you should understand the economic problem involved. I have statistics, I have graphs, I have . . .”

“But that would be putting the clock back. Have you no idea of progress, or development?”

Caspian’s response could have come out of the mouths of any of the millions of people who lack the connections and – let’s say moral flexibility – to thrive in government:

In other words, you don’t need [slaves]. Tell me what purpose they serve except to put money into the pockets of such as [the slave trader] Pug? . . . . I do not see that it brings into the islands meat or bread or beer or wine or timber or cabbages or books or instruments of music or armour or anything else worth having. But whether or not it does, it must be stopped.

So, two action items here. First, for anyone in congress who was holding off on enacting meaningful financial reform until you were clear on Narnia’s position on the matter, you may now proceed.

Second, speaking now to the British Royal Family from the self-governing former colony of America, if you can tear yourself away from hanging out with pedophiles and dressing up like Nazis, maybe you could come over and visit Wall Street and kick a little Gumpass, if you know what I mean.

Now, I’m certain that some readers are going to feel that I’ve played a bit fast and loose with the analogy here. After all, is it really fair to compare contemporary American capitalism to the slave trade?

You make a good point, imaginary critic.

Here in America, we live in one of the richest nations in the history of the world. The top one percent of the population receive only 25% of the income and control only 40% of the wealth. Government policies meet needs of corporations and the extremely wealthy with increasing efficiency. We send the children of the least wealthy members of our society off to fight against oppressive regimes that do not cater to our geopolitical dominance, while we send the children of the wealthiest members of our society off to curry favor with equally oppressive regimes that provide us with energy resources and places to dock our warships. Corporations have been granted rights of unlimited expression and privacy, while individual whistleblowers are confined and tortured. Rules of equal treatment in the court system have been abandoned for those subsets of humanity deemed too dangerous to be given a fair trial.

You’re right. It is absolutely nothing at all like slavery.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Update: I’ve changed the title, and modified the text a bit to clarify that King Caspian X is the same person as Prince Caspian, which is probably obvious only if you are a huge C. S. Lewis fan.

My wife is still much too good for me, and now has a website to prove it

So, a couple of months ago, I posted an announcement that my wife had gotten a two-book deal for her middle-grade book Remarkable. If you want to experience my going on and on about the book, I’ll just refer you back to that post. For the just-the-facts version: her agent is Faye Bender, her editor is Nancy Conescu, and the book should be coming out in 2012 under Penguin’s Dial Books imprint.

Anyway, the point of this post is to let you know about her new author website, which you can find at http://www.lizziekfoley.com. You’ll find pictures and factoids and a lot of little things that will give you a sense of the book.

|

| Who is this parrot? Is it going to eat this Basset Hound’s nose? Go to http://www.lizziekfoley.com to find out! |

So, go check it out. Then come back here and read some more blog posts. You will come away with a good sense of how lucky I got when she married me.

The Genetical Book Review: White Cat

So, welcome back to the Genetical Book Review, where we use concepts from evolutionary biology and genetics to talk about novels. In this installment, we are going to talk about White Cat, written by Holly Black. This is the first book in the Curse Workers fantasy series, the second book of which is set to be published in April. Holly Black may be familiar to some readers as one of the authors of The Spiderwick Chronicles.

|

| Artist imitates art. Holly Black dons eponymous gloves in an effort not to accidentally curse herself when she touches her face. Image from the Holly Black website. |

|

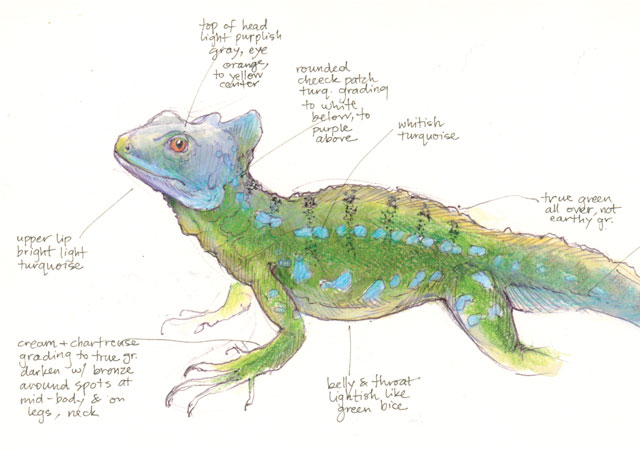

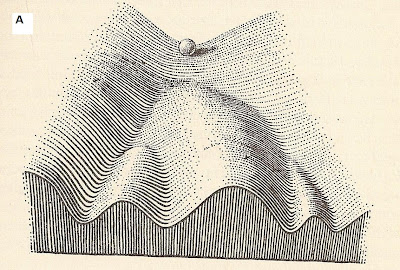

| Waddington represented development as a ball following one of a set of distinct, stereotyped pathways, like the character arcs on “reality” television. |

|

| A Plinko contestant drops a hockey-puck type thing onto a board with a bunch of pegs on it to determine which kind of curse work he will spend his life doing. Genetics works exactly like this. |

WADDINGTON, C. (1942). Canalization of Development and the Inheritance of Acquired Characters Nature, 150 (3811), 563-565 DOI: 10.1038/150563a0

Update: I had originally described the book as having been written by Michael Frost and Holly Black, which is what it says on the Kindle version, where I read it. Upon further investigation, it seems that Michael Frost is responsible for the cover art, but not the writing in the book. Everywhere else, Holly Black is the only listed author, so I have corrected my review accordingly. It strikes me as odd that the only place where he would be listed as a co-author is on the Kindle, where there is no cover art, but there you have it.

Buy it now!!

What’s that? You say you want to buy this book? And you want to support Lost in Transcription at the same time? Well, for you, sir and/or madam, I present these links.

Buy White Cat now through:

Happy Birthday, Kenneth Koch

So, yesterday (February 27) would have been Kenneth Koch‘s 81st birthday, had he not passed away in 2002. He is among the poets that I find I can always go back to when I grow tired of poetry. He is associated with the “New York School” of the 50s and 60s, which included Frank O’Hara, John Ashberry, and James Schuyler. He is reasonably well known, although not super famous, in part, I think, because he sort of falls in the gap between the two main categories that define contemporary American poetry.

For simplicity, we could call these two categories “high art” and “popular,” although I am sure that more accurate and more descriptive terms exist. On the one hand, much contemporary poetry seems to be written primarily for consumption by other poets. It grapples with language and imagery in a way that is often self-consciously designed to challenge the reader. Typically, unless you read a lot of poetry, this work tends not to be a lot of fun, and it can be hard to distinguish between good and bad versions of it.

On the other hand, we have poetry that is self-consciously aimed at a popular audience, maybe people who haven’t read a poem since high school. This work tends to be playful with language, reveling in rhyming or puns, and is accessible on a first read (Maya Angelou or Billy Collins would be examples). These poets tend not to be valued highly by academics and poets (typically the same people), in part because these poems tend to give you everything they have on that first reading, yielding little additional satisfaction on rereading.

Koch’s poetry is part of a movement that was deliberately reacting against the dense, highly referential poetry of, say, Eliot, and trying to recapture the playfulness of language. In this sense, he is a progenitor of the contemporary popular strain of American poetry. On the other hand, he was often motivated by very artsy, high-culture things, like abstract expressionist painting (which was still high art in the 1950s) and music.

To my mind, this position, straddling popular and high art, is an admirable place to aim for. The ideal poem would be one that welcomes the reader with something that is broadly accessible, whether sound or humor or imagery. At the same time, there should be layers that nag at the reader, encouraging them to return to the poem, and giving them a glimpse of something new on each read.

What I love most about Koch, however, is his emotional stance. Probably ninety percent of the poetry in the world is either about poetry, or about being sad or mistreated. At least half of it is about being a sad or mistreated poet. Throughout his career, Koch kept returning to the project of writing poems about happiness. This is a dangerous thing to do, because you set the bar higher for yourself when you write about being happy. You especially open yourself up to being criticized for sentimentality when you dare to write about simple, universal sources of happiness, like having your wife sit on your lap. But again and again, in my opinion, at least, he set himself a high happy-poem bar and then cleared it.

In honor of Koch’s birthday, and the example he set both for how to live a happy life and how to write poetry about it, I wanted to share this poem of mine from Transistor Rodeo. It is a pseudo-sestina prompted by a passage in Koch’s poem “Days and Nights.” The sestina form consists of six six-line stanzas that use the same six end words. The end words occur in a prescribed order in each stanza. The poem ends with a three-line stanza that also contains these six words. In this pseudo-sestina, I have followed the canonical pattern in terms of the order in which the six words are used, but have used a different transformation rule on each word to introduce variation each time it comes up. Only the word “dream” is repeated in the standard way.

Tomorrow, Utah – The Day After Tomorrow, well, also Utah

So, tomorrow I am headed to Salt Lake City for a poetry reading. I’ll be reading from my book, Transistor Rodeo, as well as some newer poems, primarily from a series called Thus in the Limit, which tackles the topic of immigration. If you’re in the Salt Lake area please come by!

The reading will be on Thursday (Feb 24) at 7 pm. The location is: Finch Lane Gallery/Art Barn, 1340 East 100 South, SLC, UT. There will also be a “noontime conversation” at the same location on Friday at – let me check – noon. Both events are free and open to the public.

I’ll be reading with Ander Monson, who has published books of poetry and essays, which are worth reading, and I am certain will be worth hearing as well. I’m not sure how to describe Ander’s work, so I’ll describe him instead.

When you first see his name, you’re like “Ander Monson! That’s awesome. It’s just like ‘Another Monsoon.'”

Then, you meet him, and you’re like “He so totally should have been named ‘Another Monsoon.'”

Then, you find out that his twitter is @angermonsoon, and you’re like “Anger Monsoon! What did I tell you? See, it’s perfect! What! No, why, what did you think I said? No, ‘Anger Monsoon’ is so much better than ‘Another Monsoon.’ Why would I say ‘Another Monsoon’? That’s just dumb.”

Also, he is a connoisseur of beer, which already makes him one of America’s Heroes, but more importantly, he recognizes that many microbrews lazily try to make their beer fancy by just adding more hops, which is sort of like trying to make your poetry better by just making it less comprehensible.

Anyway, his writing is sort of like the kind of thing that that guy would write. Come to the reading, and you’ll see what I mean.

Grass und Gaga – Im Ei

So, here’s something you probably already know, but wish you didn’t. Lady Gaga showed up at the Grammy Awards last night in an outfit that, in evolutionary terms, represents a sort of neoteny relative to the meat dress she was sporting at the MTV Video Music Awards. Here she is arriving. She’s the one you can’t see, because she is inside the egg.

|

| Lady Gaga is carried inside an egg by four of her muscular servants, who are so poorly paid that two of them can not even afford shirts. Later, the slave-mistress would mount the egg and let out guttural screams until the singer emerged, soaked in amniotic fluid. At least, I am assuming that is what happened. Image via CBS News. |

But really, I just wanted to use this as an excuse to share a poem that I love. It is by Günter Grass, and is probably a reasonable approximation of what Lady Gaga was muttering to herself in a Gollum-like rasp while contemplating which of her servants she would consume first. The difference is that she would no doubt be muttering in the original German, whereas I am presenting you with an English translation, taken here from the 1977 bilingual edition of In the Egg and Other Poems. The English translation of this poem was done by Michael Hamburger.

Enjoy!

In The Egg

We live in the egg.

We have covered the inside wall

of the shell with dirty drawings

and the Christian names of our enemies.

We are being hatched.

Whoever is hatching us

is hatching our pencils as well.

Set free from the egg one day

at once we shall make an image

of whoever is hatching us.

We assume that we’re being hatched.

We imagine some good-natured fowl

and write school essays

about the colour and breed

of the hen that is hatching us.

When shall we break the shell?

Our prophets inside the egg

for a middling salary argue

about the period of incubation.

They posit a day called X.

Out of boredom and genuine need

we have invented incubators.

We are much concerned with our offspring inside the egg.

We should be glad to recommend our patent

to her who looks after us.

But we have a roof over our heads.

Senile chicks,

polyglot embryos

chatter all day

and even discuss their dreams.

And what if we’re not being hatched?

If this shell will never break?

If our horizon is only that

of our scribbles, and always will be?

We hope that we’re being hatched.

Even if we only talk of hatching

there remains the fear that someone

outside our shell will feel hungry

and crack us into the frying pan with a pinch of salt.

What shall we do then, my brethren inside the egg?

Reflected Glory: Agha Shahid Ali

So, I’m a few days late with this post, as I had intended for it to coincide with Agha Shahid Ali’s birthday, but there you have it. Had he not passed away in 2001, he would have turned 61 on February 4.

Although I never had the opportunity to meet him, I feel personally indebted to him, and sad that I did not know him. My poetry book was published last year after it won the 2009 Agha Shahid Ali Poetry Prize. Since then, I have had a number of conversations with people who did know him, and they invariably go on and on about what a fantastic human being he was. And it’s not at all in the way that people tend to speak well of the dead. In every one of these conversations, people speak in an almost trance-like state. Their voices and eyes soften, as if his immense kindness were channeled through them.

He was born and raised in Kashmir, attended the Universities of Kashmir and Delhi, and then came to the United States, where he earned a PhD from Penn State and an MFA from the University of Arizona. He taught at creative writing programs across the country, leaving behind a trail of devoted students and colleagues.

He wrote several books of poetry, but is perhaps best known for his championing of the ghazal, an ancient Arabic poetic form that dates back to like the 6th century. It long ago spread across southern Asia, and has become a common form in Persian and Urdu poetry. He translated a collection of ghazals by Faiz Ahmed Faiz into English, and his best-known work is probably his posthumously published collection Call Me Ishmael Tonight: A Book of Ghazals.

The ghazal form consists of a series of couplets, where the second line of each couplet ends with a sort of extended rhyme. What I mean by that is that there are one or a few words at the end of the line that are repeated exactly in each couplet, preceded by a conventional rhyme. It also conventionally contains the poet’s name in the last couplet. Agha Shahid Ali’s most famous ghazal is the title(ish) poem “Tonight” from his posthumous collection. You can find it easily on the internet, and you should.

Here is his poem “Land,” where you can see the ghazal form as well as the soul of the man who was so well loved.

Land

For Christopher Merrill

Swear by the olive in the God-kissed land –

There is no sugar in the promised land.

Why must the bars turn neon now when, Love,

I’m already drunk in your capitalist land?

If home is found on both sides of the globe,

home is of course here – and always a missed land.

Clearly, these men were here only to destroy,

a mosque now the dust of a prejudiced land.

Will the Doomsayers die, bitten with envy,

when springtime returns to our dismissed land?

The prisons fill with the cries of children.

Then how do you subsist, how do you persist, Land?

“Is my love nothing for I’ve borne no children?”

I’m with you, Sappho, in that anarchist land.

A hurricane is born when the wings flutter …

Where will the butterfly, on by wrist, land?

You made me wait for one who wasn’t even there

though summer had finished in that tourist land.

Do the blind hold temples close to their eyes

when we steal their gods for our atheist land?

Abandoned bride, Night throws down her jewels

so Rome – on our descent – is an amethyst land.

At the moment the heart turns terrorist,

are Shahid’s arms broken, O Promised Land?

Egypt Week – I, Too, Sing Egypt

So, this will be a non-science Egypt Week post. Opposition organizers in Egypt have called for a massive protest on Tuesday, anticipating that millions will march on Tahrir Square in the morning. Here is hoping that this leads to better things.

Below is the text of the Langston Hughes poem I, Too, Sing America. While it was obviously written in the context of racial dynamics and inequality in the United States, its sense of hope, defiance, and the inevitability of justice speaks for oppressed and dismissed people everywhere.

I, too, sing America.

I am the darker brother.

They send me to eat in the kitchen

When company comes,

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong.Tomorrow,

I’ll be at the table

When company comes.

Nobody’ll dare

Say to me,

“Eat in the kitchen,”

Then.Besides,

They’ll see how beautiful I am

And be ashamed–I, too, am America.

Peace be upon you.

Yes, I married up

So, for those of you who know us personally, this will not come as a surprise, because you already know that my wife is a hundred times smarter and more talented than I am. But here’s the new news. She has just sold her book manuscript, Remarkable, to Dutton publishing as part of a two-book deal. Other authors in their list includes authors ranging from Ken Follett and Eckhart Tolle to John Hodgman and Jenny McCarthy. Their backlist includes, among other classics, the Winnie-the-Pooh books.

Remarkable is a middle-grade reader, which, as I understand it, is the age group just below young adult. I think that this is approximately the same group as the Harry Potter and Percy Jackson books. Or, if you’re actually familiar with the genre, the Mysterious Benedict Society books.

I don’t want to give anything away, other than to say that it is the BEST FREAKING BOOK YOU WILL EVER READ IN YOUR LIFE, EVER. The target age group is, technically, 9-12, so buy it for your kids. But, like all the best children’s literature, it has layers of nuance in its themes and characters that will engage adult readers.

Obviously, I’m not an unbiased reviewer here, but this book moved to tears and to laugh out loud – sometimes at the same time – and even after reading multiple previous drafts.

For those in the population genetics community, you can look forward to a cameo appearance by John Novembre.

The editor is hoping to include the book in Dutton’s Spring 2012 catalog. When more information becomes available, I’ll pass it along.

If you’re connected to her on Facebook or Twitter, say hi and congratulations, because she’ll no doubt be too modest to adequately blow her own horn (yet another way in which she is a hundred times better than I am). Or, stop by her sadly neglected blog and say hi in the comments.

From me, congratulations Lizzie K. Foley!! You deserve everything good that is coming to you. And congratulations to her agent, Faye Bender, and her brand-new editor, Nancy Conescu!