In the wake of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia’s death, Republicans have been climbing all over each other like a less well intentioned pile of zombies in an effort to most loudly claim that President Obama has no right to appoint his successor. Most of the arguments have focused on the fact that we have now entered the final year of Obama’s presidency. As you will recall, back in 2012, the ballots for president clearly stated that the results would only be construed as representing the will of the people for the next three years.

Obviously, these arguments fail any non-disingenuous reading of the constitutional and historical evidence (and contradict arguments previously made by many of those same Republicans), but, you know, the constitution, like the bible, is sacred, infallible, and beyond scrutiny — except when it turns out to be politically inconvenient.

But at the most recent Republican debate, everyone’s favorite cingulocidal maniac Ben Carson offered a different argument:

Well, the current constitution actually doesn’t address that particular situation, but the fact of the matter is the Supreme Court, obviously, is a very important part of our governmental system. And, when our constitution was put in place, the average age of death was under 50, and therefore the whole concept of lifetime appointments for Supreme Court judges, and federal judges was not considered to be a big deal.

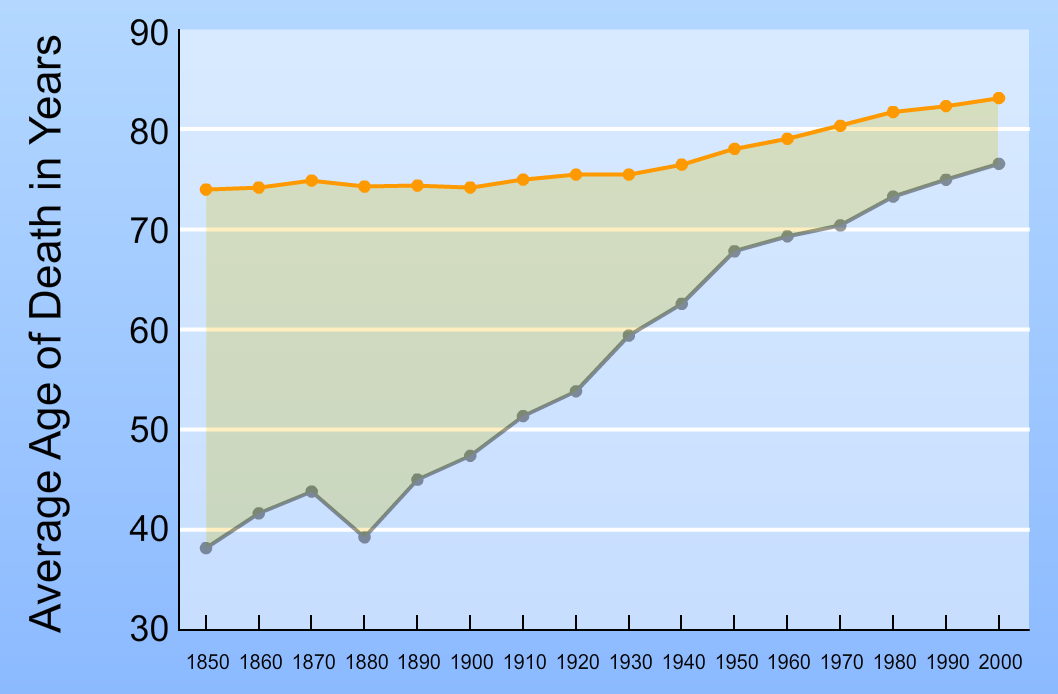

Carson is correct that the “average age of death” used to be under 50. In fact, it did not exceed 50 until sometime in the early 20th century. However, as anyone with any educational background in public health or medicine might be expected to know, the dramatic gains in life expectancy have come mostly from reductions in early-life mortality, due to things like sewers, vaccines, and antibiotics. So, unless the Founding Fathers were appointing toddlers to the Supreme Court (spoiler: they weren’t), life expectancy at birth is pretty irrelevant. Here are a couple of graphs (generated here):

The gray line is life expectancy at birth from 1850 to 2000. The orange and red lines are life expectancy from age 60 for women and men, respectively. Since people are not typically appointed to the supreme court until they are in their 50s, this is actually the relevant data.

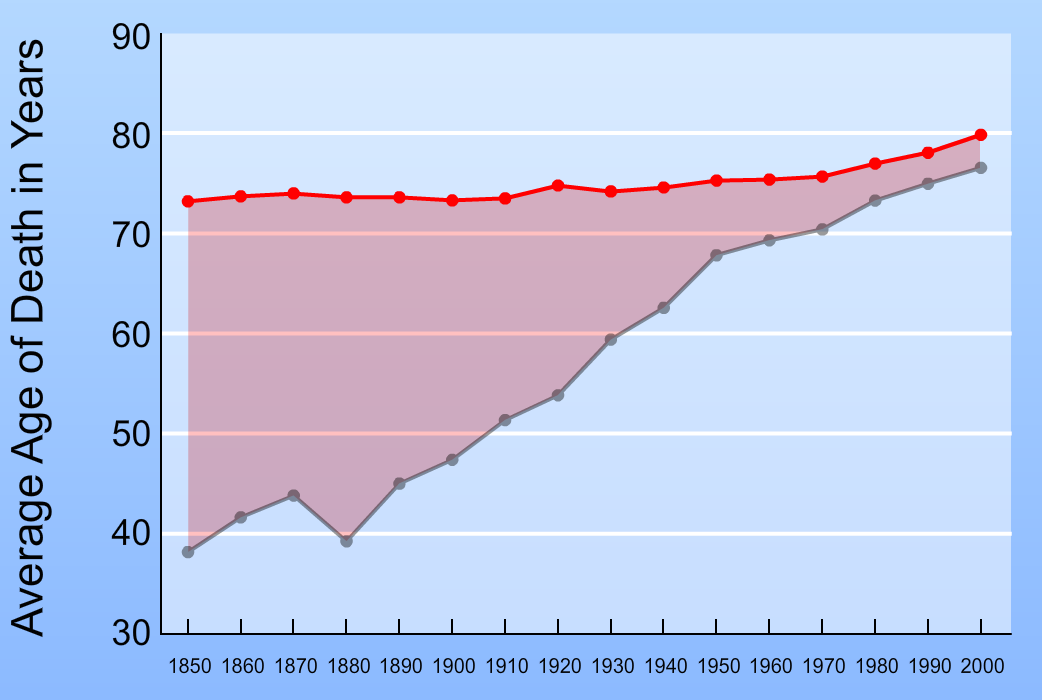

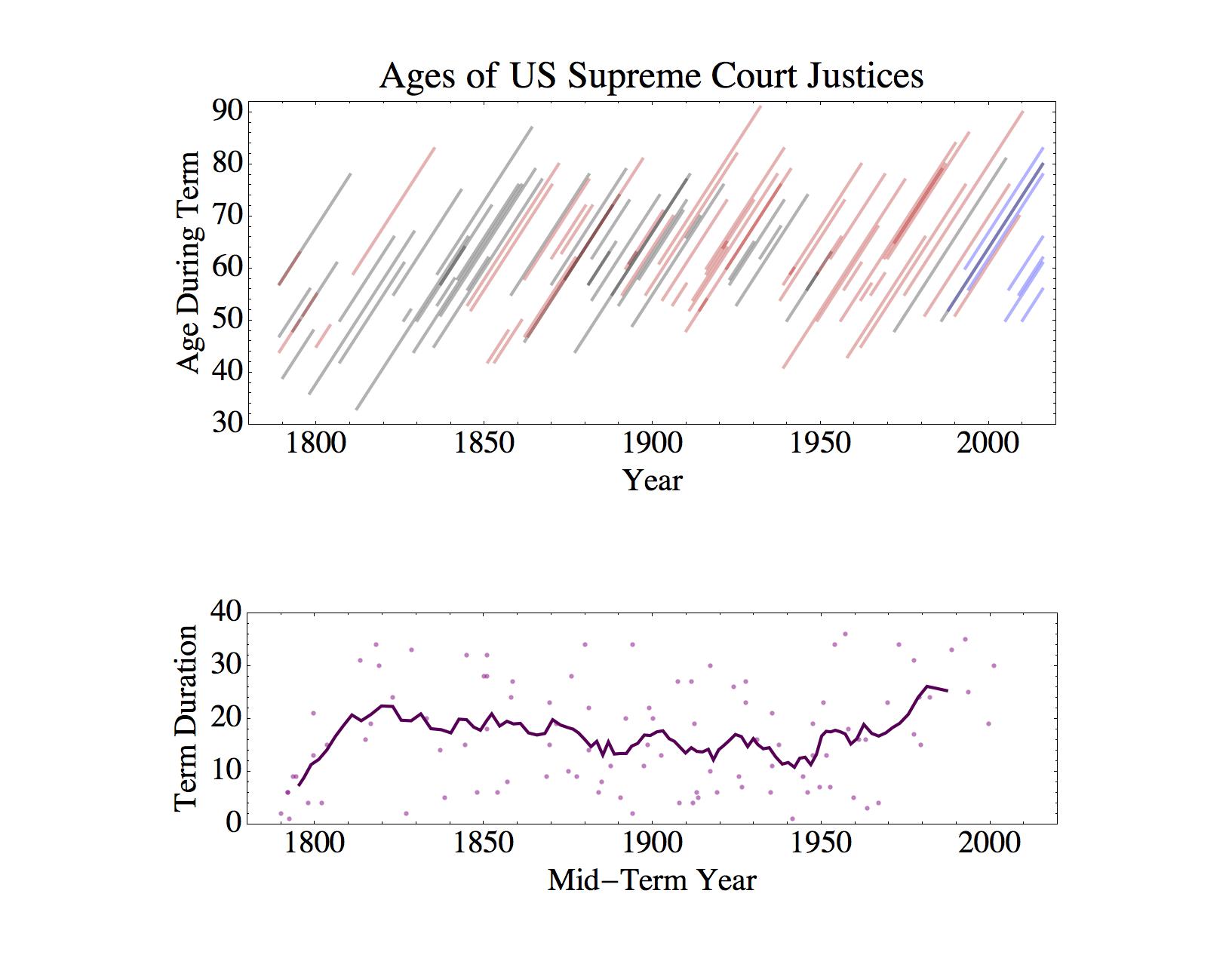

So, it is true that someone appointed to the supreme court today might be expected to live longer on average than someone appointed in the 19th century, but only by about ten years. But does that mean that justices given lifetime appointments to the supreme court serve longer than they used to? Not so much. Here are a couple more graphs, constructed from this data:

In the top panel, each diagonal line indicates the term of a single Supreme Court Justice, running from the date and age of appointment to age date and age of death or retirement. The black lines are justices who died in office, red lines are justices who resigned or retired, and blue lines are the eight justices currently serving.

In the bottom panel, each dot represents a single justice. “Mid-Term Year” is the halfway point of their tenure (middle of the line in the top graph), and duration is how long they served (length of the line in the top graph. The line is a ten-point moving average. Current justices are not included.

Notice that justices were not often dying by age 50, even in the early days. There are a couple of interesting trends, though.

First, there’s a transition as we get into the 20th century, when it becomes much more common for justices to retire, rather than die in office. So, while the upper limit on the age we might expect a justice to live to might have increased by about ten years, the upper limit on the age at which they leave the court has not changed substantially in 200 years.

Second, after an initial shake-out (during which many of the justices did not have any sort of legal credentials), the long-term trend from 1820 to 1950 is towards shorter average term lengths (declining from around 20 to around 15 years). Starting with the second half of the 20th century, the trend has been towards longer tenures, with a recent average closer to 25 years. However, if you look at the scatter plot, you can see that this increase is mostly due to the absence of any short-term justices since 1970.

So, it is true that we should probably expect that the next person appointed to the Supreme Court will be there for the next twenty to thirty years, but terms of that length have been around since the beginning.

What is cingulocidal?