So, thanks to the Harvey Weinstein story, sexual harassment is in the news again. The specific context this time is the entertainment industry, but it may well remind you of the ongoing endemic harassment in academia. In fact, there are some structural similarities between the two industries that make them prone to this sort of abuse.

Both are industries where there are far more people aspiring to careers in the industry than there are top-tier positions. For another, both rely heavily on patronage systems. Plus, both are imperfect meritocracies: favoritism and connections play huge roles in career success, but there is enough real meritocracy to provide a degree of plausible deniability.

Previously, I provided some guidelines for people in academia who are thinking about pursuing a colleague. If you think of yourself as being a genuinely “good guy” who wants to make sure you don’t cross the line, give them a read. But here are a few additional points to consider.

Point 1: Your workplace is not a singles’ bar

Whenever a case of sexual harassment comes up, one of the inevitable knee-jerk defenses is concern trolling about policing behavior in the workplace. “You can’t stand in the way of human nature!” “But what about true love?” Or, from Woody Allen, you need to avoid a “witch hunt,” where “every guy in an office who winks at a woman is suddenly having to call a lawyer to defend himself.”

The implication is always that if we stop people from “flirting” in the workplace, we will somehow be standing in the way of romance. Like, if you cut people off from hitting on their co-workers, they will all die alone.

If you’re an academic looking for romance, good luck to you! But do it someplace where the expectation is that other people are also looking for romance. Whether you’re looking for a life partner or a hook-up, there are plenty of apps and meet-ups and clubs and bars that people use as vehicles to meet romantic partners. Make use of one of those.

That is, when you go to work, you should be going to work. And you should assume that the other people there are there for the purpose of working. If you wink at someone at a singles’ bar, they may or may not be interested in you, but it is reasonable to assume that they have come to the bar open to the possibility of meeting someone. At work, that is not a reasonable assumption.

Now one of the defenses that gets wheeled out in academia is that it is natural to date people in your lab, or department, because you naturally have shared interests. Well, that’s what your Tinder profile is for, jackass. (“Passionate about long walks on the beach and invertebrate neuronal development!”) Plus, anecdotally speaking, the people I have heard articulating this excuse are almost entirely people with reputations for inappropriate behavior. So, don’t be that guy.

Point 2: If you’re dating “down,” you’re not actually looking for romance

In hierarchical systems like academia (or the entertainment industry), social relationships almost always have a strong hierarchical element. Even if two people are not in a direct supervisory relationship, there is very often a big power imbalance. Typically, one person is more senior, respected, connected, and generally influential than the other. Most academic fields are small enough that alienating a senior member of the field can do huge damage to your career, even if that person is at another institution.

People on the receiving end of this power imbalance are well aware of it, and they get a lot of advice, so I’d like to speak for a moment to the folks in a position of power:

Stop it.

If you’re a professor hitting on grad students, or postdocs, just stop. Yes, I’m sure you’re having some sort of crisis that is entirely sympathetic in an Updike/Roth sort of way, and I promise not to judge you harshly if you go out and buy a motorcycle. But quit hitting on people who are below you in the hierarchy.

If you’re a fifty-something man hitting on a twenty-something woman who works for you, the best-case scenario is that you are desperately grasping after your lost youth, that you’ve been conditioned to view younger women as sexually desirable, that you’ve been seduced by a narcissistic fantasy of academically and sexually mentoring a younger version of yourself.

And look, that’s pretty bad. But it still begs the question of why you’re looking in your own department, instead of going online. The answer is that you don’t want a relationship with an equal. You want a relationship with someone who can’t say no. The power differential is a guarantee of success.

And, of course, for many of you, the relationship is not even the primary goal. The goal is simply the exercise of power, whether you are embarking on a coercive relationship, or just seeing how many hugs and back rubs you can get away with. You’re like a toddler knocking over a tower of blocks, engorged by your own ability to make change in the world.

Stop it.

Point 3: People with power need to start putting themselves out there

There are a lot of good reasons why people who get harassed don’t speak up. Typically, they are in positions of little power, which is part of why they were targeted in the first place. For bystanders, the impulse to value peace over justice means that many people, including people who would never be harassers, will actively seek reasons to minimize or justify what happened. As a result, people who speak out about harassment, whether as victims or witnesses, often pay a very real price for that.

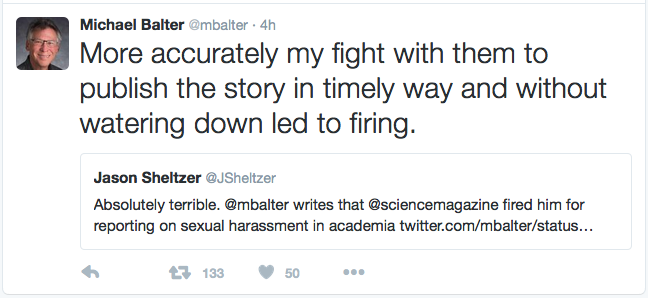

So, each person needs to decide for themselves whether or not they are willing to pay that price. And victims, in particular, should not be pressured to do so. However, if you have a position of power, where you have the ability to speak up on behalf of victims, you need to be honest with yourself about what that price actually is.

Here’s the thing. If you’re a student, speaking up may mean the end of your career, even if you are vindicated by the process. And that’s a heavy price to pay. But if you’re a professor, particularly one with tenure, you are in no such position. Yes, speaking up may cost you professionally. You may get invited to fewer conferences. You may get your grants funded at a lower rate. But other than in extraordinary circumstances, your career and livelihood are not likely to be in jeopardy.

Most people I know in academia are good, well intentioned people, people who do not actively participate in bad things. However, most are also extremely reluctant to speak publicly about injustice if there is a chance that there will be any sort of negative impact on their careers. And somehow we tend to act like that’s okay, like every professor is Jean Valjean, with a sister whose children will starve if they report a serial harasser to the Dean.

We need to acknowledge that yes, there is a cost associated with speaking out. But once you’ve made it past a certain point in academia, you can afford to pay that cost.

A lot of you went into your field in order to make the world a better place. Here’s your chance.