So, remember when not all kids books were about teenage wizards and sexy vampires? Well, it turns out that, if you know where to look, you can still find books like that. Enter The Mapmaker and the Ghost, by Sarvenaz Tash.

[Disclaimer: Sarv is a friend of my wife’s. They got to know each other through the fact that both are in the New York area, and both had their debut middle-grade novels come out this year. If you are concerned that this may color the objectivity of this review, may I refer you to the Genetical Book Review’s premise and guidelines.]

The Mapmaker and the Ghost is a story that I would say is of the same general flavor as something like From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler. The setting is very much our world, and the adventure is on a human scale. In the Mixed-Up Files, a girl and her younger brother run off to the museum, and get caught up in a quest to discover the provenance of a statue. In Mapmaker, a girl (Goldenrod) and her younger brother (Birch) find adventure in the woods at the edge of town, and get caught up in a quest to find a legendary blue rose.

|

| The Mapmaker and the Ghost, by Sarvenaz Tash. Want to buy it already? Settle down there, sparky! Purchase links will be available at the bottom of the post. |

For kids, I think, the human scale makes the story directly relatable to their own lives. At least, that seems to be one of the things that our kid loved about the book. (He was nine at the time he first read it, and has reread it multiple times.) The concerns that the characters have, about curfews and money and permission to go past a certain point in the street, etc., seem to resonate with the experience of childhood in a way that very few authors pull off.

Of course, as in any good adventure, there are exciting things that happen that go well beyond what most children actually experience. But those events have an emotional impact that derives from the realism of the novel. I mean, saving the world from the most evil villain of all time is, of course, exciting, but evading the gaze of a security guard can actually be even more emotionally tense and exhilarating, because it is a situation that a young reader can really embody.

Also, there’s a gang of semi-feral kids with names like “spitbubble” and “snotshot,” a mysterious old lady, a secret lair, and, of course, a ghost.

The book is appropriate for ages 7 through probably about 12. The main character is a girl, but the novel is strongly gendered, and will be engaging for boys and girls. (If you have a son who thinks that they should not read a book like this because it is about a girl, you should definitely buy it, thump him over the head with it, and then watch him enjoy it anyway.)

Now, on with the science!

As I mentioned, the central quest in the novel is the search for a blue rose that blooms in the woods at the edge of town once every fifty years. This is a big deal, because, you know, roses aren’t blue. When you find a rose that is actually blue, it’s blue because it has been dyed blue.

A few years ago, a Japanese company called Suntory made news when they produced the world’s first non-dyed blue rose. They managed this through genetic engineering, taking a gene from a pansy and inserting it into a rose. [Insert juvenile and inappropriate joke here.]

Now, you’re probably looking at this rose and thinking that you have to be pretty colorblind (or have a job in Suntory’s marketing division) to call this “blue.” Fair enough, but, that’s the state of the art at the moment.

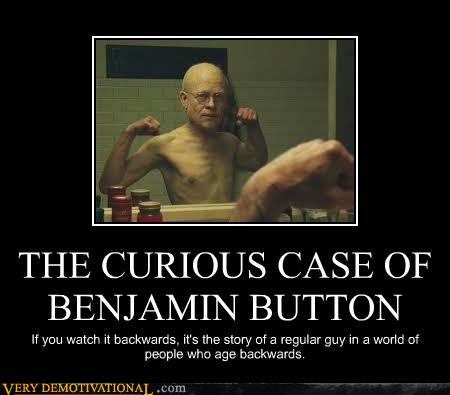

|

| Suntory’s “blue” rose, which, while lilac a best, is still pretty cool. As an aside, we could also interpret this as an example of what linguists call “collocational restriction,” where the term “blue” has an idiomatic meaning in the specific context of the phrase “blue rose.” In this case, it might be interpreted as “bluer than a rose normally is,” much as “white coffee” is not actually white, but is at the white end of the distribution of coffee colors. (Image via Wired) |

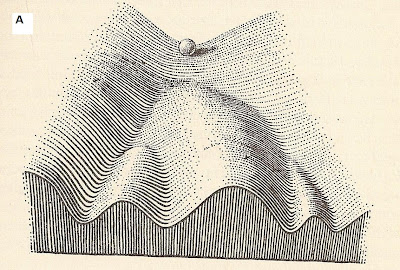

Here is Figure 1 from the publication of Suntory’s work, which shows the biosynthetic pathways responsible for plant color. You don’t find blue roses in nature because roses lack an enzyme in the pathway on the far right, which means that they lack any delphinidin-based anthocyanins.

|

| Anthocyanins are the primary chemicals responsible for |

The gene that the researchers inserted into the rose is the one indicated by F3’5’H in the figure. This enzyme (flavonoid 3′,5′-hydroxylase) is normally absent from roses, which is why they lack the bluish pigments.

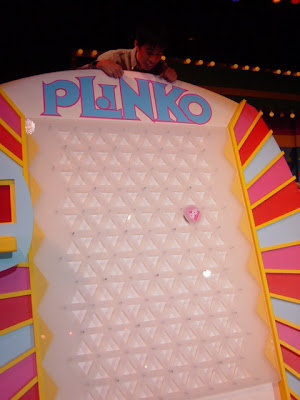

Although only one blue rose cultivar has been brought to market (The Suntory “Applause” pictured above), they actually did the transformation with a bunch of different cultivars. Here are a few examples (from the same paper).

|

| In each panel, the flowers on the left are without the F3’5’H gene, and the ones on the right are with it. |

If you read Japanese (or trust Google Translate), you can check out more information at Suntory’s dedicated blue-rose webpage, which features topics such as “Legend,” “Brand Concept,” and “Applause Wedding” (new!).

The authors note that there are various things one could imagine doing to make roses even bluer, including tinkering with the pH, getting other pigments in there, etc. How easy these next steps are going to be is less clear, though. It’s hard to tinker without breaking stuff. Perhaps genuinely blue roses will continue to be the symbol of unattainability, and limited to great kids’ books.

Katsumoto, Y., Fukuchi-Mizutani, M., Fukui, Y., Burgliera, F., Holton, T. A., Karan, M., Nakamura, N., Yonekura-Sakakibara, K., Togami, J., Pigeaire, A., Tao, G.-Q., Nehra, N. S., Lu, C.-Y., Dyson, B. K., Tsuda, S., Ashikari, T., Kusumi, T., Mason, J. G., & Tanaka, Y. (2007). Engineering of the Rose Flavonoid Biosynthetic Pathway Successfully Generated Blue-Hued Flowers Accumulating Delphinidin Plant Cell Physiol., 48 (11), 1589-1600 DOI: 10.1093/pcp/pcm131

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Buy it now!!

What’s that? You say you want to buy this book? And you want to support Lost in Transcription at the same time? Well, for you, sir and/or madam, I present these links.

Buy The Mapmaker and the Ghost now through: