So, this starts off cute, but gets progressively more awesome. I love that part of the mechanism for turning the newspaper page involves knocking a laptop onto the floor.

Show, don’t tell. The Brindley lecture on erectile dysfunction

So, if you’ve ever taken a creative writing class or workshop, you’ve undoubtedly been enjoined to “show,” rather than “tell.” It’s one of those writing rules that is commonplace to the point of being cliche. In fact, many instructors feel sufficiently self-conscious about offering that advice that they feel obliged to provide caveats. You know, sometimes telling is the right thing to do, and, of course, it depends on how you tell. Blah, blah, blah.

I’m hoping that this blog has at least one reader who has taken a writing course in Japan, because I’m curious as to what the analogous rule is there. Based on a non-comprehensive sampling of dating simulators, manga comics, and Murakami novels, I imagine generations of Japanese MFA students being told “Tell, don’t show!” You know, “Hi, my name is Haruki. I often come off as brash, but underneath it I am actually quite shy. Also, I had a good, healthy bowel movement this morning.”

Anyway, speaking of “show, don’t tell,” I just came across this brief memoir, published in 2005 by Laurence Klotz in the British Journal of Urology International. He fondly recalls a lecture by G. S. Brindley at the 1983 Urodynamics Society meeting in Las Vegas. Brindley had just made a breakthrough in the treatment of erectile dysfunction through self-injection with papaverine. [Note, I don’t know where the “self-injection” has to be.] After showing a series of photographs of erect penises, Brindley wanted to demonstrate that the effect was not the result of a confounding erotic environment:

The Professor wanted to make his case in the most convincing style possible. He indicated that, in his view, no normal person would find the experience of giving a lecture to a large audience to be erotically stimulating or erection-inducing. He had, he said, therefore injected himself with papaverine in his hotel room before coming to give the lecture, and deliberately wore loose clothes (hence the track-suit) to make it possible to exhibit the results. He stepped around the podium, and pulled his loose pants tight up around his genitalia in an attempt to demonstrate his erection.

At this point, I, and I believe everyone else in the room, was agog. I could scarcely believe what was occurring on stage. But Prof. Brindley was not satisfied. He looked down skeptically at his pants and shook his head with dismay. ‘Unfortunately, this doesn’t display the results clearly enough’. He then summarily dropped his trousers and shorts, revealing a long, thin, clearly erect penis. There was not a sound in the room. Everyone had stopped breathing.

But the mere public showing of his erection from the podium was not sufficient. He paused, and seemed to ponder his next move. The sense of drama in the room was palpable. He then said, with gravity, ‘I’d like to give some of the audience the opportunity to confirm the degree of tumescence’. With his pants at his knees, he waddled down the stairs, approaching (to their horror) the urologists and their partners in the front row. As he approached them, erection waggling before him, four or five of the women in the front rows threw their arms up in the air, seemingly in unison, and screamed loudly.

“I’d like to give some of the audience the opportunity to confirm the degree of tumescence.” Scientific meetings used to be so awesome.

I believe that I found this a couple of days ago via a Twitter or Google+ link, but I’ve lost the origin now. Apologies to the original poster/tweeter. If you know who it is (e.g., if it’s you), please let me know in the comments, and I’ll update with credit.

William Shatner goes Space Truckin’

So, if you slept through October, you might have missed the release of William Shatner’s latest “music” album Seeking Major Tom. It features some very, very Shatner covers a bunch of space-themed songs, like “Rocket Man,” along with a bunch of stuff-that’s-sort-of-vaguely-related-to-space-themed songs, like “She Blinded Me with Science.”

Of the few that I have listened to, my favorite is this cover of Deep Purple’s “Space Truckin,” here set to some awesome space-themed choreography by intrepid YouTuber zanderkaneusa:

This cake is my prisoner

So, this is a really short video of animated magnetic poetry tiles. It’s kind of awesome.

I especially love the way that “no” works here. It is hard – but interesting – to imagine how one could achieve a similar effect with fixed text on a page.

Enjoy.

Help me out with this fortune cookie

So, you know how you’re supposed to be able to take any fortune cookie fortune and add “in bed” to it? Okay, I just got back from having Chinese food, and I’m trying to figure out what it would mean when we add “in bed” to this one:

Remember to order your take out also?

I’m hoping somebody can help me out here. What’s your best guess as to how to unpack:

Remember to order your take out also? In bed?

There has to be a meaningful, puerile interpretation wrapped up in there somewhere. Calling for suggestions.

This is why we can’t have nice things, Denver

So, quick quiz. You’re in a new museum, one that is named after and dedicated to a prominent abstract expressionist painter, looking at one of said painter’s masterworks. Do you:

A) Nod knowingly while noting how the work eschews traditional figurative representation in an effort to access a rawer, more visceral, emotional universality.

B) Daydream about wealth, fame, and the day that whatever it is you’ve been doing in your basement for all these years will have its own museum.

C) Comment loudly that it looks like something that your five-year-old daughter could have painted.

D) Punch and scratch the painting, pull down your pants and rub your ass on it, then fall down and pee on yourself.

If you answered “D” you might be Carmen Tisch, 36-year-old art participant, who did just this to Clyfford Still’s “1957-J no.2” on December 29 at the Clyfford Still Museum in Denver.

|

| Carmen Tisch. Vandal, or performance artist? You be the judge. Image via MSNBC. |

While the painting’s value is estimated at somewhere between 30 and 40 million dollars (by the museum, so, you know, grain of salt), damage is estimated at around $10,000. Not so bad, really. Also, according to the Denver Post:

“It doesn’t appear she urinated on the painting or that the urine damaged it, so she’s not being charged with that,” said Lynn Kimbrough, a spokeswoman for the Denver District Attorney’s Office, said Wednesday.

So, that’s good news, I guess.

|

| 1957-J no.2, but before or after the ass rubbing? |

Ivar Zeile, a gallery owner in Denver, was quoted by the Post as saying that the painting can probably be restored, but, “It does damage the piece, though, even people just knowing that happened,” which is like, what? Dude, I guarantee you that prior to this incident, 99% of Americans had never heard of Clyfford Still. If anything, this woman just dramatically increased the value of the piece.

Actually, the museum ought to be paying her a commission for adding an awesome narrative to a piece of art that would not otherwise be of interest to the vast majority of the public. The fact is, a whole bunch of people will probably go into the museum now who would not have before. A few of them are going to look around and say, “Hey, this stuff is actually pretty cool.”

Thank you, Carmen Lucette Tisch. You’re like the drunk, pantsless Bill Nye of mid-century American abstract expressionism.

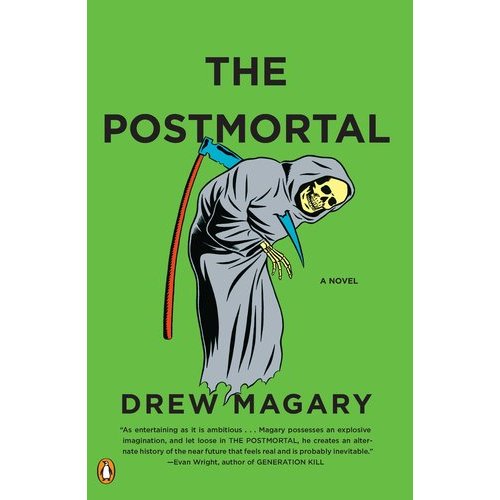

The Genetical Book Review: The Postmortal

So, welcome to the first Genetical Book Review of 2012, where we’re going to talk about The Postmortal, by Drew Magary. As the book starts, Science!™ has developed a cure for aging, so that people can live forever. What follows is an exploration of the psychological and sociological consequences of immortality.

|

| I love this picture. You can almost hear Death going, “D’oh.” |

I don’t think I’m giving anything away when I tell you that the book winds up being predominantly dystopian. Basically, if you are the sort of person who frets about the future of humanity, who is prone to think things like, “How could I possibly bring a child into this world,” well, don’t read this book. At least, don’t read it in bed after a spicy take-out meal.

If you do enjoy the occasional sci-fi dystopia, this one is of the variety where you make only a small technological (or, in this case, medical) change, and explore the implications in a world that is otherwise very much like our own. One of the interesting things that the author gets to do with this particular premise is to follow history over many decades through the eyes of a single, first-person narrator. So, the protagonist experiences technological and societal changes that would normally take place over the course of generations.

The book is presented as a series of blog posts, some of which are personal, narrative entries, and some transcripts of news reports, others link roundups, and so on. Magary is a contributing editor at Deadspin, and his reporting / media background shows through in the writing. The whole book is engaging, but the writing really shines in the news bits, which are pitch-perfect.

In the book, the cure for aging is achieved through gene therapy, targeted at a single locus, which seems to be closely linked to MC1R, the gene most commonly responsible for redheadedness. What we’re going to use this as a jumping-off point to talk about different evolutionary theories of aging, and the extent to which each might be consistent with the existence of a single gene serving as a master control over the aging process.

|

| In The Postmortal, the cure for aging is discovered serendipitously as a byproduct of research aimed at changing hair color. In our actual dystopia, it would have gone differently. Benjamin Button would have been indefinitely detained under NDAA and selectively bred with normal humans. A series of backcrosses would have been used to isolate the gene responsible for his aging reversal. |

But first, a couple of quibbles.

Quibble number 1. There are two biologists who feature prominently in the book: father and son Graham and Steven Otto. Now, I’m not going to argue sexism on the basis of a sample of two, since, even in a world with full gender equality, a random sample of two scientists would both be male about 1/4 of the time (p = 0.25). However, Graham Otto’s devoted wife (and Steven Otto’s loving mother) is (apparent) non-scientist Sarah Otto. It just so happens (presumably unbeknownst to Magary) that there is a real-life Sarah Otto, a prominent biologist who was just awarded a Macarthur “genius” grant. So, that’s . . . unfortunate.

Quibble number 2. The “cure for aging” as presented in the book arrests an individual at whatever age they are when they receive the cure, whether it is three or eighty-three. This actually conflates two different processes: development and senescence. My biological intuition is that, even in the simplest conceivable case, there would be at least two distinct master switches controlling these very different processes. (Actually, possibly a third switch as well, controlling puberty and the onset of secondary sexual characteristics, as distinct from growth to adult size and shape.)

In talking about evolutionary theories of “aging,” I will focus on evolutionary theories of senescence, which is really the most important aspect of “aging” with respect to this book.

[Note: none of this should be interpreted as a criticism of the premise or execution of the book, which I loved. The inherent power of science fiction comes from the idea that you build a world that differs from our own. Rather, as always with The Genetical Book Review, the book’s premise serves as an excuse and a specific context for talking about evolution.]

Basically, there are three major classes of ideas about the evolutionary origins of senescence, which have different implications for how much and how easily natural selection or medical intervention might be able to extend our lifespans. As is often the case, these different theories are not necessarily mutually exclusive or incompatible, but rather have different emphases. Most consistent with the premise of the book are theories that propose a positive adaptive value to senescence and mortality. Somewhat less consistent are theories that focus on senescence as a byproduct of the fact that natural selection becomes weaker for traits that are expressed later in life. Least consistent are theories suggesting that senescence and lifespan are profoundly constrained by biological universals. We’ll take each of these in turn.

|

| Just as youth is wasted on the young, discounts are wasted on the elderly. |

1) Senescence as an adaptation.

The idea that there could be a single genetic master switch controlling senescence is most plausible under models where aging and death are specifically adaptive. How would that work, you ask. I mean, after all, the whole idea behind natural selection is that is favors surviving and reproducing, right? Well, in some models, you can actually identify conditions where it makes sense beyond a certain age for adults to go ahead and die. One particular model (cited below) describes an adaptive benefit (at the group / inclusive fitness level) to senescence from limiting the spread of disease.

Perhaps somewhat more generally applicable are models in which senescence is selectively favored as part of a trade off. The idea is that it would be possible to construct a human who lived to be, say, 150, but that it could only be achieved through some sort of compensatory change in another trait. Candidate examples would be size or reproductive output. In fact, all else being equal, smaller humans do tend to live longer than larger ones. Similarly, there are a handful of studies purporting to show that abstaining from reproduction extends lifespan.

In this sort of case, it is easy to see how natural selection might actually favor earlier senescence. To first order, what matters to evolution is how many offspring you produce. If you can grow big and have lots of kids, you’re going to win the evolutionary race, even if it means that you drop dead of a heart attack at thirty-five.

Under one of these models, it is easy to imagine the existence of one or a few genes that function as controllers, or strong modifiers, of senescence. Under the strongest version, you can even imagine a gene affecting only senescence. Under the weaker, trade-off version, it might be possible to dramatically extend lifespan, but not without side effects. Maybe the immortals would all weigh eighty pounds and have dramatically – or indefinitely – delayed onset of reproductive capacity.

|

| In a world dominated by evolutionary trade-offs, the immortals will all be Romanian. |

2) Senescence as the absence of selection.

Imagine one trait that affects the probability that you survive to age ten. Now imagine a second trait that affects the probability that you survive from ten to twenty. Whatever selection is acting on the second trait, it has to be weaker than what is acting on the first one. The reason is that the second trait is under selection only in that subset of the population that survives to be ten.

This argument, of course, blends into the trade-off argument introduced earlier. We can imagine traits that trade off health (and survival) at later ages in exchange for enhanced health at earlier ages. In general, such traits will tend to be favored. Basically, it doesn’t matter how robust you are at eighty if you die at twenty.

Even without such tradeoffs, however, we expect to see natural selection growing weaker with age. Given any rate of death (due to choking on litchi nuts, falling off cliffs, being eaten by tigers, whatever), there will be more people alive at age x than at age x + y, for any y > 0. So, the older you are, the less power natural selection has to fight against entropy – both the familiar entropy of the physical world and the evolutionary entropy of the mutation process.

Some of the evidence in support of this idea comes from the fact that there are certain species that tend to live longer than expected. Included among these are birds, porcupines, and humans. What do those have in common? The reason in each case is different, but each has a reduced rate of predation. If you reduce the death rate, you increase the power of selection to slow down the aging process.

One consequence of this is that we expect all of the different systems that make up our bodies to fail at similar rates. For instance, if the human heart just gives out after 100 years, any and all selection goes away for maintaining anything else (brain, kidneys, liver, etc.) for longer than that. This perspective suggests that there will not be a single tweak that could stop aging. Rather, it would require a whole bunch of tweaks, or maybe something more like a Never-Let-Me-Go-style organ harvesting scheme.

3) Senescence as a fundamental constraint.

These ideas come from the existence of certain universal scaling laws, regularities in the relationship between features like body mass, metabolic rate, and lifespan. There are a lot of ideas out there, but what, exactly, is driving these relationships is not yet understood. However, the relationships themselves seems to be fairly robust.

One of the striking findings in this area is the fact that, among species with a heart, an individual’s lifespan corresponds to about 1.5 billion heartbeats. Small species have fast metabolic rates, fast heartbeats, and short lives. Large species live slower and longer.

Once again, these ideas are not mutually exclusive with the “rates of predation” idea. In fact, when we say that species like birds and humans live “longer than expected,” these scaling relationships determine what “expected” is. For instance, a human with a heartrate of 72 beats per minute might live to have about 3 billion heartbeats.

Whatever the origin of these patterns, their apparent universality suggests the existence of very deep constraints on our biology. While natural selection (or medicine) might be able to alter our lifespans, it may be that such intervention is limited to relatively small changes, maybe a factor of two. Perhaps something human sized that could live for many hundreds of years would have to be based on a fundamentally different biological architecture.

|

| Following the 2012 Mayan-Zombie/Santorum-Paul apocalypse, humans and other land-based vertebrates will become extinct. Eventually, cephalopod-based land dwellers will eventually emerge to fill our vacated ecological niche. Perhaps they will live longer. Image via Chowgood’s Deviant Art page. |

So, overall, I think the likelihood of a single medical advance that dramatically increases our natural lifespans is pretty remote. But, as you’ll see if you read the book, that might be for the best.

Here are just a few references to get you started if you are interested in the evolutionary constraints on lifespan and senescence.

Glazier, D. (2008). Effects of metabolic level on the body size scaling of metabolic rate in birds and mammals Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 275 (1641), 1405-1410 DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0118

Mitteldorf J, & Pepper J (2009). Senescence as an adaptation to limit the spread of disease. Journal of theoretical biology, 260 (2), 186-95 PMID: 19481552

Williams, G. C. (1957). Pleiotropy, Natural Selection, and the Evolution of Senescence Evolution, 11 (4), 398-411

Well, that’s all for today! Check back again soon, as The Genetical Book Review will be posting more frequently in 2012.

Buy it now!!

What’s that? You say you want to buy this book? And you want to support Lost in Transcription at the same time? Well, for you, sir and/or madam, I present these links.

Buy The Postmortal now through:

Happy New Year Animation ft. King Taro and Pita

So, I don’t know what to say about this video, except that it seems pretty cool, and it seems to espouse the multi-cultural, trans-national spirit of goodwill that we all ought to be embracing for these last few months before the Mayan Zombies come after us.

This was made for last year’s New Year by King Taro. The singer is Pita.

Like the pocket!

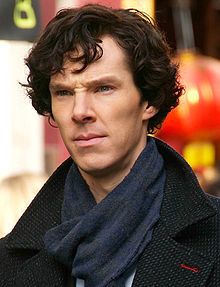

Sherlock / Smaug reads Kubla Khan

So, the official title of this is “Benedict Cumberbatch reads Kubla Khan,” but if you’re like me, you’re all, “Who the hell is Benedict Cumberbatch? That sounds like either a good way to ruin poached eggs, or some sort of sexually transmitted fungal infection.”

To save you from embarrassment, I’ll just tell you. He’s this dude:

|

| image from Wikipedia |

That’s the actor who plays Sherlock Holmes in the most recent incarnation from the BBC, Sherlock.

He’s also going to be playing the dragon Smaug in the upcoming Hobbit movies (via motion capture), and providing the voice for the Necromancer (aka Sauron). In those same movies, Bilbo Baggins will be played by Martin Freeman. Freeman also plays Watson opposite Cumberbatch’s Holmes.

Somehow the whole situation seems Oedipal to me, although I can’t quite articulate why.

Anyway, here is Cumberbatch reading Kubla Khan, one of my favorites. It is embedded here as a YouTube video, but is just audio.

If you’re watching it with the sound off, but want to know what the experience would be like if you could actually hear it, here are a few comments from YouTube:

“I want to be these words. His voice practically caresses them.”

“I would gladly go to that pleasure dome if he was in it.”

“me gusta”

“OVARIES GO BOOM!!!!!!”

1971 Bukowski letter on poetry reading

So, I’m not a huge fan of Charles Bukowski’s poetry, but the dude wrote some awesome letters. This one was posted yesterday at Boing Boing. It is his response to a request to perform a poetry reading.

Just check out that last paragraph:

I’m working on my 2nd. novel now, THE POET, but I’m taking my time. They say it’s 101 [degrees] today. Fine then, I’m drinking coffee and rolling cigarettes and looking out at the hot baked street and a lady just walked by wiggling it in tight white pants, and we are not dead yet.

You read that in a letter and it is smoking-hot prose that makes you want to go get drunk with the guy. That’s a paragraph that could only be written by the coolest person you know. But somehow, his poetry all sounds exactly like that. And, for me at least, in the context of a “poem,” I would probably feel that it was trying to hard. Or, rather, trying too hard in some ways and not hard enough in others. Maybe it is the extra expectation that is placed on words when you call them a poem, or maybe the sense of deliberateness that it implies. I’m not sure.

I think when I read that paragraph as a spontaneous statement, it crackles, but if I assume that it is deliberately crafted art, the crackle goes away. It makes me wonder if it would seem as compelling if it were written in 2001, rather than 1971, using a word processor rather than a typewriter. Maybe even the typo in “degrees” is key in conveying the authenticity / spontaneity of the statement.

Anyway, Mark Frauenfelder at Boing Boing got the letter from the tumblr this isn’t happiness, which is full of cool stuff. If you don’t already follow it, you should. Here are just a few of many, many gems to be found there (arranged roughly from FTW to WTF):