So, last week featured a lot of news about a paper that came out in the Quarterly Review of Biology titled “Homsexuality as a Consequence of Epigenetically Canalized Sexual Development.” The authors were Bill Rice (UCSB), Urban Friberg (Uppsala U), and Sergey Gavrilets (U Tennessee). The paper got quite a bit of press. Unfortunately, most of that press was of pretty poor quality, badly misrepresenting the actual contents of the paper. (PDF available here.)

I’m going to walk through the paper’s argument, but if you don’t want to read the whole thing, here’s the tl;dr:

This paper presents a model. It is a theory paper. Any journalist who writes that the paper “shows” that homosexuality is caused by epigenetic inheritance from the opposite sex parent either 1) is invoking a very non-standard usage of the word “shows,” or 2) was too lazy to read the actual paper, and based their report on the press release put out by the National Institute for Mathematical and Biological Synthesis.

That’s not to say that this is a bad paper. In fact, it’s a very good paper. The authors integrate a lot of different information to come up with a plausible biological mechanism for epigenetic modifications to exert influence on sexual preference. They demonstrate that such a mechanism could be favored by natural selection under what seem to be biologically realistic conditions. Most importantly, they formulate their model into with clear predictions that can be empirically tested.

But those empirical tests have not been carried out yet. And, in biology, when we say that a paper shows that X causes Y, we generally mean that we have found an empirical correlation between X and Y, and that we have a mechanistic model that is well enough supported that we can infer causation from that correlation. This paper does not even show a correlation. It shows that it would probably be worth someone’s time to look for a particular correlation.

As a friend wrote to me in an e-mail,

I found it a much more interesting read than I thought I would from the press it’s getting, which now rivals the bullshit surrounding the ENCODE project for the most bullshitty bullshit spin of biology for the popular press. A long-winded-but-moderately-well-grounded-in-real-biology mathematical model does not proof make.

Exactly.

Okay, now the long version.

The Problem of Homosexuality

The first thing to remember is that when an evolutionary biologist talks about the “problem of homosexuality,” this does not imply that homosexuality is problematic. All it is saying is that a straightforward, naive application of evolutionary thinking would lead one to predict that homosexuality would not exist, or would be vanishingly rare. The fact that it does exist, and at appreciable frequency, poses a problem for the theory.

In fact, this is a good thing to keep in mind in general. The primary goal of evolutionary biology is to understand how things in the world came to be the way they are. If there is a disconnect between theory and the world, it is ALWAYS the theory that is wrong. (Actually, this is equally true for any science / social science.)

Simply put, heterosexual sex leads to children in a way that homosexual sex does not. So, all else being equal, people who are more attracted to the opposite sex will have more offspring than will people who are less attracted to the opposite sex.

[For rhetorical simplicity, I will refer specifically to “homosexuality” here, although the arguments described in the paper and in this post are intended to apply to the full spectrum of sexual orientation, and assume more of a Kinsey-scale type of continuum.]

The fact that a substantial fraction of people seem not at all to be attracted to the opposite sex suggests that all else is not equal.

Evolutionary explanations for homosexuality are basically efforts to discover what that “all else” is, and why it is not equal.

There are two broad classes of possible explanation.

One possibility is that there is no biological variation in the population for a predisposition towards homosexuality. Then, there would be nothing for selection to act on. Maybe the potential for sexual human brain simply has an inherent and uniform disposition. Variation in sexual preference would then be the result of environmental (including cultural) factors and/or random developmental variation.

This first class of explanation seems unlikely because there is, in fact, a substantial heritability to sexual orientation. For example, considering identical twins who were raised separately, if one twin is gay, there is a 20% chance that the other will be as well.

|

| Evidence suggests that sexual orientation has a substantial heritable component. Image: Comic Blasphemy. |

This points us towards the second class of explanation, which assumes that there is some sort of heritable genetic variation that influences sexual orientation. Given the presumably substantial reduction in reproductive output associated with a same-sex preference, these explanations typically aim to identify some direct or indirect benefit somehow associated with homosexuality that compensates for the reduced reproductive output.

One popular variant is the idea that homosexuals somehow increase the reproductive output of their siblings (e.g., by helping to raise their children). Or that homosexuality represents a deleterious side effect of selection for something else that is beneficial, like how getting one copy of the sickle-cell hemoglobin allele protects you from malaria, but getting two copies gives you sickle cell anemia.

It was some variant of this sort of idea that drove much of the research searching for “the gay gene” over the past couple of decades. The things is, though, those searches have failed to come up with any reproducible candidate genes. This suggests that there must be something more complicated going on.

The Testosterone Epigenetic Canalization Theory

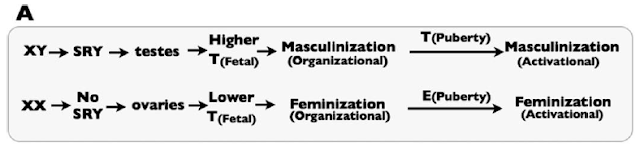

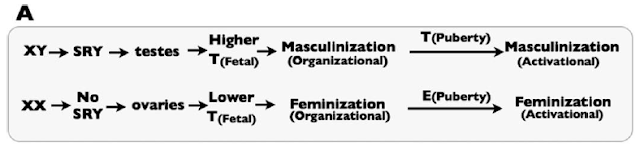

Sex-specific development depends on fetal exposure to androgens, like Testosterone and related compounds. This is simply illustrated by Figure 1A of the paper:

|

| Figure 1A from the paper: a simplified picture of the “classical” view of sex differentiation. T represents testosterone, and E represent Estrogen. |

SRY is the critical genetic element on the Y chromosome that triggers the fetus to go down the male developmental pathway, rather than the default female developmental pathway. They note that in the classical model of sex differentiation, androgen levels differ substantially between male and female fetuses.

The problem with the classical view, they rightly argue, is that androgen levels are not sufficient in and of themselves to account for sex differentiation. In fact, there is some overlap between the androgen levels between XX and XY fetuses. Yet, in the vast majority of cases, the XX fetuses with the highest androgen levels develop normal female genitalia, while the XY fetuses with the lowest androgen levels develop normal male genitalia. Thus, there must be at least one more part of the puzzle.

The key, they argue, is that tissues in XX and XY fetuses also show differential response to androgens. So, XX fetuses become female because they have lower androgen levels and they respond only weakly to those androgens. XY fetuses become male because they have higher androgen levels and they respond more strongly to those androgens.

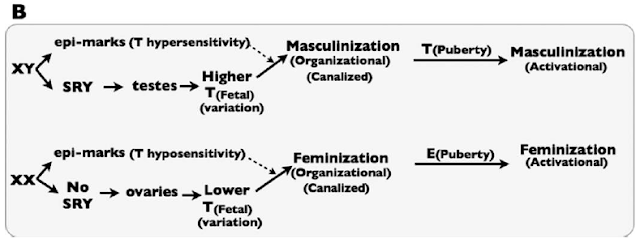

This is illustrated in their Figure 1B:

Sex-specific development is thus canalized by some sort of mechanism that they refer to generically as “epi-marks.” That is, they imagine that there must be some epigenetic differences between XX and XY fetuses that encode differential sensitivity to Testosterone.

All of this seems well reasoned, and is supported by the review of a number of studies. It is worth noting, however, that we don’t, at the moment, know exactly which sex-specific epigenetic modifications these would be. One could come up with a reasonable list of candidate genes, and look for differential marks (such as DNA methylation or various histone modifications) in the vicinity of those genes. However, this forms part of the not-yet-done empirical work required to test this hypothesis, or, in the journalistic vernacular, “show” that this happens.

Leaky Epigenetics and Sex-Discordant Traits

Assuming for the moment that there exist various epigenetic marks that 1) differ between and XX and XY fetuses and 2) modulate androgen sensitivity. These marks would need to be established at some point early on in development, perhaps concurrent with the massive, genome-wide epigenetic reprogramming that occurs shortly after fertilization.

The theory formulated in the paper relies on two additional suppositions, both of which can be tested empirically (but, to reiterate, have not yet been).

The first supposition is that there are many of these canalizing epigenetic marks, and that they vary with respect to which sex-typical traits they canalize. So, some epigenetic marks would canalize gonad development. Other marks would canalize sexual orientation. (Others, they note, might canalize other traits, like gender identity, but this is not a critical part of the argument.)

|

| The model presented in this paper suggests that various traits that are associated with sex differences may be controlled by distinct genetic elements, and that sex-typical expression of those traits may rely on epigenetic modifications of those genes. Image: Mikhaela.net. |

The second supposition is that the epigenetic reprogramming of these marks that normally happens every generation is somewhat leaky.

There are two large-scale rounds of epigenetic reprogramming that happen every generation. One occurs during gametogenesis (the production of eggs or sperm). The second happens shortly after fertilization. What we would expect is that any sex-specifc epigenetic marks would be removed during one of these phases (although it could happen at other times).

For example, a gene in a male might have male-typical epigenetic marks. But what happens if that male has a daughter? Well, normally, those marks would be removed during one of the reprogramming phases, and then female-typical epigenetic marks would be established at the site early in his daughter’s development.

The idea here is that sometimes this reprogramming does not happen. So, maybe the daughter inherits an allele with male-typical epigenetic marks. If the gene influences sexual orientation by modulating androgen sensitivity, then maybe the daughter develops the (male-typical) sexual preference for females. Similarly, a mother might pass on female-typical epigenetic marks to her son, and these might lead to his developing a (female-typical) sexual preference for males.

So, basically, in this model, homosexuality is a side effect of the epigenetic canalization of sex differences. Homosexuality itself is assumed to impose a fitness cost, but this cost is outweighed by the benefit of locking in sexual preference in those cases where reprogramming is successful (or unnecessary).

Sociological Concerns

Okay, if you ever took a gender-studies class, or anything like that, this study may be raising a red flag for you. After all, the model here is basically that some men are super manly, and sometimes their manliness leaks over into their daughters. This masculinizes them, which makes them lesbians. Likewise, gay men are gay because they were feminized by their mothers.

That might sound a bit fishy, like it is invoking stereotype-based reasoning, but I don’t think that would be a fair criticism. Nor do I think it raises any substantial concerns about the paper in terms of its methodology or its interpretation. (Of course, I could be wrong. If you have specific concerns, I would love to hear about them in the comments.) The whole idea behind the paper is to treat chromosomal sex, gonadal sex, and sexual orientation as separate traits that are empirically highly (but not perfectly) correlated. The aim is to understand the magnitude and nature of that empirical correlation.

The other issue that this raises is the possibility of determining the sexual orientation of your children, either by selecting gametes based on their epigenetics, or by reprogramming the epigenetic state of gametes or early embryos. This technology does not exist at the moment, but it is not unreasonable to imagine that it might exist within a generation. If this model is correct in its strongest form (in that the proposed mechanism fully accounts for variation in sexual preference), you could effectively choose the sexual orientation of each of your children.

This, of course, is not a criticism of the paper. The biology is what it is. It does raise certain ethical questions that we will have to grapple with at some point. (Programming of sexual orientation will be the subject of the next installment of the Genetical Book Review.)

Plausibility/Testability Check

The question one wants to ask of a paper like this is whether it is 1) biologically plausible, and 2) empirically testable. Basically, my read is yes and yes. The case for the existence of mechanisms of epigenetic canalization of sex differentiation seems quite strong. We know that some epigenetic marks seem to propagate across generations, evading the broad epigenetic reprogramming. We don’t understand this escape very well at the moment, but the assumptions here are certainly consistent with the current state of our knowledge. And, assuming some rate of escape, the model seems to work for plausible-sounding parameter values.

Testing is actually pretty straightforward (conceptually, if not technically). Ideally, empirical studies would look for sex-specific epigenetic modifications, and for variation in these modifications that correlate with variation in sexual preference. The authors note that one test that could be done in the short term would be to do comparative epigenetic profiling of the sperm of men with and without homosexual daughters.

As Opposed to What?

The conclusions reached by models in evolution are most strongly shaped by the set of alternatives that are considered in the model. That is, a model might find that a particular trait will be selectively favored, but this always needs to be interpreted in the context of that set of alternatives. Most importantly, one needs to ask if there are likely to be other evolutionarily accessible traits that have been excluded from the model, but would have changed the conclusions of the model if they had been included.

The big question here is the inherent leakiness of epigenetic reprogramming. A back-of-the-envelope calculation in the paper suggests that for this model to fully explain the occurrence of homosexuality (with a single gene controlling sexual preference), the rate of leakage would have to be quite high.

An apparent implication of the model is that there would then be strong selection to reduce the rate at which these epigenetic marks are passed from one generation to the next. In order for the model to work in its present form, there would need to be something preventing natural selection from finding this solution.

Possibilities for this something include some sort of mechanistic constraint (it’s just hard to build something that reprograms more efficiently than what we have) or some sort of time constraint (evolution has not had enough time to fix this). The authors seem to favor this second possibility, as they argue that the basis of sexual orientation in humans may be quite different from that in our closest relatives.

On the other hand this explanation could form a part of the explanation for homosexuality with much lower leakage rates.

What Happened with the Press?

So, how do we go from what was a really good paper to a slew of really bad articles? Well, I suspect that the culprit was this paragraph from the press release from NIMBios:

The study solves the evolutionary riddle of homosexuality, finding that “sexually antagonistic” epi-marks, which normally protect parents from natural variation in sex hormone levels during fetal development, sometimes carryover across generations and cause homosexuality in opposite-sex offspring. The mathematical modeling demonstrates that genes coding for these epi-marks can easily spread in the population because they always increase the fitness of the parent but only rarely escape erasure and reduce fitness in offspring.

If you know that this is a pure theory paper, this is maybe not misleading. Maybe. But phrases like “solves the evolutionary riddle of homosexuality” and “finding that . . . epi-marks . . . cause homosexuality in opposite-sex offspring,” when interpreted in the standard way that I think an English speaker would interpret them, pretty strongly imply things about the paper that are just not true.

Rice, W., Friberg, U., & Gavrilets, S. (2012). Homosexuality as a Consequence of Epigenetically Canalized Sexual Development The Quarterly Review of Biology, 87 (4), 343-368 DOI: 10.1086/668167

Update: Also see this excellent post on the subject by Jeremy Yoder over at Nothing in Biology Makes Sense.