So, welcome back to the Genetical Book Review! This episode? The Psychopath Test, by Jon Ronon. Ronson is the author of The Men Who Stare at Goats, which the movie was based on.

Also, his name is what my name would be if I were from Iceland.

The Psychopath Test traces Ronson’s exploration of psychopathy: what a psychopath is, how you identify one, the effect they have on society, and society’s efforts to contain them. The book is written engagingly, and makes for a quick read, even if you’re as slow a reader as I am. Ronson mixes historical and medical information with interviews of both psychopaths and the doctors who have sought to define and/or treat them. Some of the accounts, you can imagine, touch on some fairly gruesome events, but the light manner of the writing should make the material palatable even for those with weaker stomachs for that sort of thing.

One of the most interesting things about the book is the fact that the material is presented chronologically — not in the order that things happened, but in the order that Ronson learned about and understood them (ostensibly, at least). The effect is a really interesting one, which fits well with what seems to be one of the books goals. By the end of the book, Ronson has deconstructed the whole notion of sanity/insanity, as well as the motives of doctors, pharmaceutical companies, police, the entertainment industry, and journalists, including himself.

He achieves the effect by writing in a sort of semi-gonzo, close first person, chronicling his own reactions and beliefs along the journey. First, he learns x, and so he believes X. Then, in the next chapter, he learns y, and starts to doubt his belief in X. And so on throughout the book. The result is a message that is fragmented, but also nuanced and faceted. This mixture of sometimes contradictory conclusions actually seems quite fitting, given the complexity of the phenomenon, and our limited understanding of it.

Even out of that complexity though, there are two big take-home messages that rise above the others.

First is the fact that psychopathy is not really a well-defined, discrete thing. There is a continuum not only of severity, but of type. Two people could both score high on the eponymous psychopath test (constructed by Bob Hare, who features prominently in the book), but actually exhibit quite different suites of behavior.

This, of course, is not news to anyone who has spent time studying psychiatric disorders (or any other sort of complex disease). Labeling is a necessary part of science and of medicine, as it is what allows us to communicate with each other in an efficient way. However, we need to keep reminding ourselves that these labels refer to abstractions, and that the thing we care about is typically a lot more complicated, and a lots less well understood, than a monolithic label implies.

Which is to say, while it might not be news, it is always good to be reminded of it.

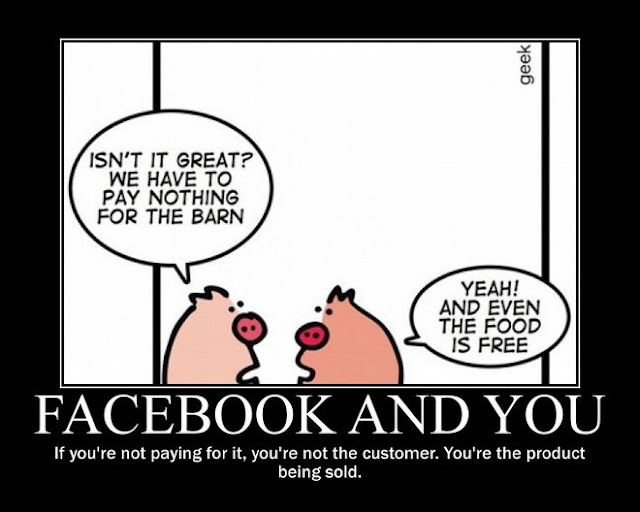

Second is the idea that there are a lot of aspects of society that have a vested interest in reducing people to their maddest edges, as Ronson puts it. Reality television and daytime talk shows seek out people who have something going on that is crazy enough to be entertaining, and then edit out all the boring (read “sane”) bits. Journalists do likewise, seeking out the extreme behaviors and personalities that will make for good quotations and compelling stories. Pharmaceutical companies benefit monetarily from the application of clinical labels to any behavior that lies outside the norm.

And so forth.

There are obviously a lot of very ill people out there. But there are also people in the middle, getting overlabeled, becoming nothing more than a big splurge of madness in the minds of the people who benefit from it.

The other thing that struck me was the chapter on the DSM, the big book that defines all mental illnesses. I think I had always assumed that there was some sort of rigorous, evidence-based process by which disorders were included or excluded. It seems that, well, not so much. It seems more like it is a veneer of codification laid on top of a bunch of idiosyncratic opinions, passed through a filter of special interests. Sigh.

Basically, if you work in the field, you may already be familiar with many of the stories, and may already have internalized many of the punchlines. But, for most people, The Psychopath Test provides an entertaining, informative, and often troubling look at medicalization and exploitation of mental health in our society.

Ronson, Jon. The Psychopath Test. New York: Riverhead Books, 2011.

Hare, R. D. (1980). A research scale for the assessment of psychopathy in criminal populations Personality and Individual Differences, 1 (2), 111-120 : 10.1016/0191-8869(80)90028-8

Buy it now!!

What’s that? You say you want to buy this book? And you want to support Lost in Transcription at the same time? Well, for you, sir and/or madam, I present these links.

Buy The Psychopath Test now through:

Amazon

Barnes and Noble

indiebound

Alibris