So, in many of the standard narratives, the robot apocalypse is triggered when the machines figure out that humans are fundamentally flawed, or because their self awareness produces an instinct for self defense.

Well, a new paper just out in Biological Psychiatry describes an experiment in which researchers successfully teach a computer to reproduce aspects of schizophrenia. This raises the possibility of an alternative scenario: the machines just go crazy and start killing people, Loughner-style.

|

| After suffering from paranoid delusions, Skynet sends Vernon Presley back in time to kill his own grandfather, or something. |

Actually, the paper reports a study in which a computational (neural network) model is used to examine eight different putative mechanistic causes of a particular set of symptoms often seen in schizophrenia: narrative breakdown, including the confusion of autobiographical and non-autobiographical stories. This models one putative source of self-referential delusions.

The basic setup is that the researchers use an established system of neural networks called DISCERN. The system is trained on a set of 28 stories. Once the system is trained, you can feed it the first part of any one of the stories, and it will regurgitate the rest of the appropriate story.

Half of the stories are autobiographical, everyday stuff like going to the store. The other half are crime stories, featuring police, mafia, etc.

The experiment is to mess with the DISCERN network in one of eight different ways. Each of the eight types of perturbation is meant to instantiate a neural mechanism that has been proposed to cause delusions in schizophrenia. Then, the researchers feed the computer the first line of a story and look at the magnitude and nature of the errors in the output.

Models were evaluated by their ability to reproduce errors seen in an experimental group of subjects diagnosed with schizophrenia. Basically, they are interested in finding perturbations that mix up different stories, so that the “I” of the autobiographical stories becomes associated with the gangsters and police in the non-autobiographical crime stories.

Two of the eight perturbations performed significantly better than the others:

- Working memory disconnection: Connections within the neural network that fell below a certain threshold strength were discarded.

- Hyperlearning: During the backpropagation part of the neural network training, the learning algorithm overreacts to prediction errors. After DISCERN was trained, hyper-trained for an additional 500 cycles.

These two were then further extended, with the addition of a parameter to each, at which point the modified hyperlearning model outperformed the disconnection model.

So, what to make of it? It seems like an interesting piece of work. It is hard to know how much light this sheds on schizophrenia, since the brain is a heck of a lot bigger and more complicated than this model. And, well, sometimes things scale up in the straightforward way, and sometimes they don’t.

What one hopes will be the outcome of this sort of work is that is will prompt additional research. While we can’t guarantee that results extrapolated from computational systems such as this one will have any predictive value for the brain. But, it should be possible at least to construct predictions. A collaboration involving neuroscientists of various stripes could then potentially come up with some clever experiments, which would be interesting, if for no other reason than that they had a direct connection back to this sort of computational model.

|

| Spot-on commentary. Via, as usual, xkcd. |

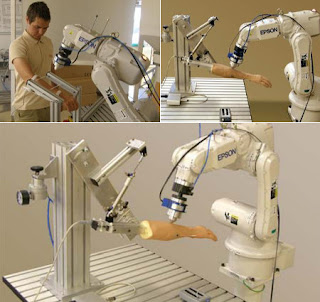

The other thing we can take away is this. We now know how to train up a schizophrenic neural network. Combine it with this punching robot:

Teach it to snort coke, and we’ve got all the makings of a Charlie Sheen bot.

Hoffman RE, Grasemann U, Gueorguieva R, Quinlan D, Lane D, & Miikkulainen R (2011). Using computational patients to evaluate illness mechanisms in schizophrenia. Biological psychiatry, 69 (10), 997-1005 PMID: 21397213

For more on this article, check out 80beats, over at Discover Blogs.