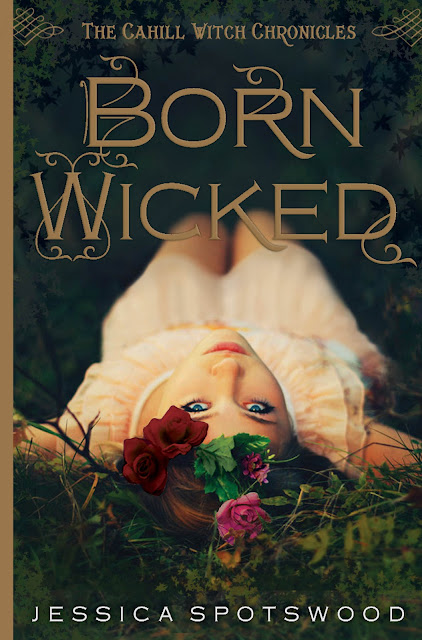

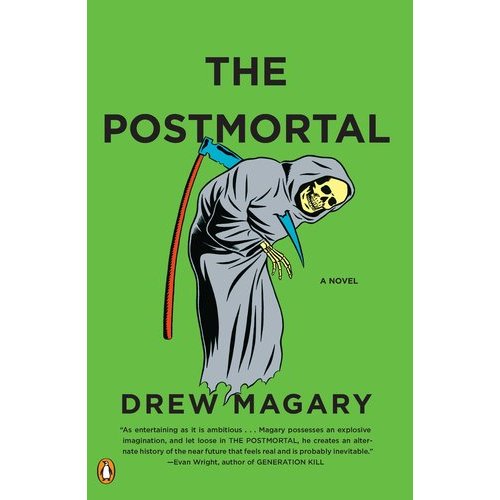

So, welcome to the first Genetical Book Review of 2012, where we’re going to talk about The Postmortal, by Drew Magary. As the book starts, Science!™ has developed a cure for aging, so that people can live forever. What follows is an exploration of the psychological and sociological consequences of immortality.

|

| I love this picture. You can almost hear Death going, “D’oh.” |

I don’t think I’m giving anything away when I tell you that the book winds up being predominantly dystopian. Basically, if you are the sort of person who frets about the future of humanity, who is prone to think things like, “How could I possibly bring a child into this world,” well, don’t read this book. At least, don’t read it in bed after a spicy take-out meal.

If you do enjoy the occasional sci-fi dystopia, this one is of the variety where you make only a small technological (or, in this case, medical) change, and explore the implications in a world that is otherwise very much like our own. One of the interesting things that the author gets to do with this particular premise is to follow history over many decades through the eyes of a single, first-person narrator. So, the protagonist experiences technological and societal changes that would normally take place over the course of generations.

The book is presented as a series of blog posts, some of which are personal, narrative entries, and some transcripts of news reports, others link roundups, and so on. Magary is a contributing editor at Deadspin, and his reporting / media background shows through in the writing. The whole book is engaging, but the writing really shines in the news bits, which are pitch-perfect.

In the book, the cure for aging is achieved through gene therapy, targeted at a single locus, which seems to be closely linked to MC1R, the gene most commonly responsible for redheadedness. What we’re going to use this as a jumping-off point to talk about different evolutionary theories of aging, and the extent to which each might be consistent with the existence of a single gene serving as a master control over the aging process.

|

| In The Postmortal, the cure for aging is discovered serendipitously as a byproduct of research aimed at changing hair color. In our actual dystopia, it would have gone differently. Benjamin Button would have been indefinitely detained under NDAA and selectively bred with normal humans. A series of backcrosses would have been used to isolate the gene responsible for his aging reversal. |

But first, a couple of quibbles.

Quibble number 1. There are two biologists who feature prominently in the book: father and son Graham and Steven Otto. Now, I’m not going to argue sexism on the basis of a sample of two, since, even in a world with full gender equality, a random sample of two scientists would both be male about 1/4 of the time (p = 0.25). However, Graham Otto’s devoted wife (and Steven Otto’s loving mother) is (apparent) non-scientist Sarah Otto. It just so happens (presumably unbeknownst to Magary) that there is a real-life Sarah Otto, a prominent biologist who was just awarded a Macarthur “genius” grant. So, that’s . . . unfortunate.

Quibble number 2. The “cure for aging” as presented in the book arrests an individual at whatever age they are when they receive the cure, whether it is three or eighty-three. This actually conflates two different processes: development and senescence. My biological intuition is that, even in the simplest conceivable case, there would be at least two distinct master switches controlling these very different processes. (Actually, possibly a third switch as well, controlling puberty and the onset of secondary sexual characteristics, as distinct from growth to adult size and shape.)

In talking about evolutionary theories of “aging,” I will focus on evolutionary theories of senescence, which is really the most important aspect of “aging” with respect to this book.

[Note: none of this should be interpreted as a criticism of the premise or execution of the book, which I loved. The inherent power of science fiction comes from the idea that you build a world that differs from our own. Rather, as always with The Genetical Book Review, the book’s premise serves as an excuse and a specific context for talking about evolution.]

Basically, there are three major classes of ideas about the evolutionary origins of senescence, which have different implications for how much and how easily natural selection or medical intervention might be able to extend our lifespans. As is often the case, these different theories are not necessarily mutually exclusive or incompatible, but rather have different emphases. Most consistent with the premise of the book are theories that propose a positive adaptive value to senescence and mortality. Somewhat less consistent are theories that focus on senescence as a byproduct of the fact that natural selection becomes weaker for traits that are expressed later in life. Least consistent are theories suggesting that senescence and lifespan are profoundly constrained by biological universals. We’ll take each of these in turn.

|

| Just as youth is wasted on the young, discounts are wasted on the elderly. |

1) Senescence as an adaptation.

The idea that there could be a single genetic master switch controlling senescence is most plausible under models where aging and death are specifically adaptive. How would that work, you ask. I mean, after all, the whole idea behind natural selection is that is favors surviving and reproducing, right? Well, in some models, you can actually identify conditions where it makes sense beyond a certain age for adults to go ahead and die. One particular model (cited below) describes an adaptive benefit (at the group / inclusive fitness level) to senescence from limiting the spread of disease.

Perhaps somewhat more generally applicable are models in which senescence is selectively favored as part of a trade off. The idea is that it would be possible to construct a human who lived to be, say, 150, but that it could only be achieved through some sort of compensatory change in another trait. Candidate examples would be size or reproductive output. In fact, all else being equal, smaller humans do tend to live longer than larger ones. Similarly, there are a handful of studies purporting to show that abstaining from reproduction extends lifespan.

In this sort of case, it is easy to see how natural selection might actually favor earlier senescence. To first order, what matters to evolution is how many offspring you produce. If you can grow big and have lots of kids, you’re going to win the evolutionary race, even if it means that you drop dead of a heart attack at thirty-five.

Under one of these models, it is easy to imagine the existence of one or a few genes that function as controllers, or strong modifiers, of senescence. Under the strongest version, you can even imagine a gene affecting only senescence. Under the weaker, trade-off version, it might be possible to dramatically extend lifespan, but not without side effects. Maybe the immortals would all weigh eighty pounds and have dramatically – or indefinitely – delayed onset of reproductive capacity.

|

| In a world dominated by evolutionary trade-offs, the immortals will all be Romanian. |

2) Senescence as the absence of selection.

Imagine one trait that affects the probability that you survive to age ten. Now imagine a second trait that affects the probability that you survive from ten to twenty. Whatever selection is acting on the second trait, it has to be weaker than what is acting on the first one. The reason is that the second trait is under selection only in that subset of the population that survives to be ten.

This argument, of course, blends into the trade-off argument introduced earlier. We can imagine traits that trade off health (and survival) at later ages in exchange for enhanced health at earlier ages. In general, such traits will tend to be favored. Basically, it doesn’t matter how robust you are at eighty if you die at twenty.

Even without such tradeoffs, however, we expect to see natural selection growing weaker with age. Given any rate of death (due to choking on litchi nuts, falling off cliffs, being eaten by tigers, whatever), there will be more people alive at age x than at age x + y, for any y > 0. So, the older you are, the less power natural selection has to fight against entropy – both the familiar entropy of the physical world and the evolutionary entropy of the mutation process.

Some of the evidence in support of this idea comes from the fact that there are certain species that tend to live longer than expected. Included among these are birds, porcupines, and humans. What do those have in common? The reason in each case is different, but each has a reduced rate of predation. If you reduce the death rate, you increase the power of selection to slow down the aging process.

One consequence of this is that we expect all of the different systems that make up our bodies to fail at similar rates. For instance, if the human heart just gives out after 100 years, any and all selection goes away for maintaining anything else (brain, kidneys, liver, etc.) for longer than that. This perspective suggests that there will not be a single tweak that could stop aging. Rather, it would require a whole bunch of tweaks, or maybe something more like a Never-Let-Me-Go-style organ harvesting scheme.

3) Senescence as a fundamental constraint.

These ideas come from the existence of certain universal scaling laws, regularities in the relationship between features like body mass, metabolic rate, and lifespan. There are a lot of ideas out there, but what, exactly, is driving these relationships is not yet understood. However, the relationships themselves seems to be fairly robust.

One of the striking findings in this area is the fact that, among species with a heart, an individual’s lifespan corresponds to about 1.5 billion heartbeats. Small species have fast metabolic rates, fast heartbeats, and short lives. Large species live slower and longer.

Once again, these ideas are not mutually exclusive with the “rates of predation” idea. In fact, when we say that species like birds and humans live “longer than expected,” these scaling relationships determine what “expected” is. For instance, a human with a heartrate of 72 beats per minute might live to have about 3 billion heartbeats.

Whatever the origin of these patterns, their apparent universality suggests the existence of very deep constraints on our biology. While natural selection (or medicine) might be able to alter our lifespans, it may be that such intervention is limited to relatively small changes, maybe a factor of two. Perhaps something human sized that could live for many hundreds of years would have to be based on a fundamentally different biological architecture.

|

Following the 2012 Mayan-Zombie/Santorum-Paul apocalypse, humans and other land-based vertebrates will become extinct. Eventually, cephalopod-based land dwellers will eventually emerge to fill our vacated ecological niche.

Perhaps they will live longer. Image via Chowgood’s Deviant Art page. |

So, overall, I think the likelihood of a single medical advance that dramatically increases our natural lifespans is pretty remote. But, as you’ll see if you read the book, that might be for the best.

Here are just a few references to get you started if you are interested in the evolutionary constraints on lifespan and senescence.

Glazier, D. (2008). Effects of metabolic level on the body size scaling of metabolic rate in birds and mammals Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 275 (1641), 1405-1410 DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0118

Mitteldorf J, & Pepper J (2009). Senescence as an adaptation to limit the spread of disease. Journal of theoretical biology, 260 (2), 186-95 PMID: 19481552

Williams, G. C. (1957). Pleiotropy, Natural Selection, and the Evolution of Senescence Evolution, 11 (4), 398-411

Well, that’s all for today! Check back again soon, as The Genetical Book Review will be posting more frequently in 2012.

Buy it now!!

What’s that? You say you want to buy this book? And you want to support Lost in Transcription at the same time? Well, for you, sir and/or madam, I present these links.

Buy The Postmortal now through:

Amazon

Barnes and Noble

indiebound

Alibris