So, you’ve probably heard that the world is ending this Saturday (or, as Tom Scocca explains, sometime between Friday evening and Sunday morning, depending on how the rapture interacts with the time zones). You may already have signed up on Facebook to attend the pre-rapture orgy and/or the post-rapture looting.

Earlier, I posted my discovery that you can be taken up by the rapture even if you’re actively engaging in gay sex when it happens, which is pretty awesome.

But now I want to talk about the timing issue.

Back in January I wrote a post making fun of Harold Camping’s claim that he knew when the rapture was coming. The biblical counter-argument comes from Matthew 24:36, which, in the standard Lolcat edition, reads:

but bout dat dai or hour no wan knows, not even teh angels in heaven, nor teh son, [e] but only teh fathr.

(The non-biblical counter-argument, of course, is, “Wait, what? That’s just stupid.”)

The punchline in my previous post was a variation of the standard one that people like myself like to drop in these situations. In this case, it was, “Look! An evolutionary biologist who was raised in a Unitarian church with an atheist minister knows more about the bible than Harold Camping! Hahahaha!”

|

| This is the bible translation favored by Lost in Transcription. |

In fact, this is just one of several places in the bible that emphasize the unpredictability of the rapture (and/or the second coming, which is maybe a different thing — who knew?).

So, what’s that about, then? What it reminds me of is the phenomenon of endgame effects in economic games. If you’re not familiar with endgame effects, well, actually you are, because it is one of those regularities that shows up in life just as much as it does in experimental economics.

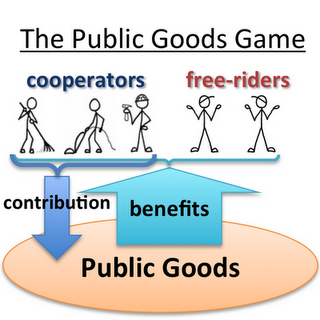

I’ll describe this in terms of a public goods game, but the phenomenon occurs in a variety of contexts. In your standard public goods game, players are given some money. Each player chooses how much of their money to contribute to a common pot. The money in the pot is then multiplied by some amount (e.g. 3X), and then divided equally among the players, without regard to whether or not they contributed.

|

| Nice picture illustrating the basic structure of a public goods game. I poached this one from Ben Allen’s blog, which would make him a cooperator, since he made this slide. I would be a defector, since I am freeloading off of his work. |

The group as a whole benefits most if everyone puts their whole endowment into the pot. But, each individual gets their best payoff if everyone else donates to the pot, but they don’t. If you run this experiment over and over, you find that people typically start off making a decent contribution (typically ~ 50%), but the contributions decline over time, until eventually pretty much everyone is putting in nothing.

A standard modification, then, is to incorporate a punishment phase after each round of the game. For example, people might be given the option to pay some money in order to have money taken away from one of the people who did not donate to the pot.

The first interesting finding that gets reproduced again and again is that people are willing to pay to punish defectors. The second standard finding is that incorporating a punishment phase stabilizes cooperation. So, given the threat of punishment, people will continue to donate to the pot at a high level.

Okay, so here’s where the endgame effect comes in. These experiments are typically set up to run a certain number of rounds. Whether the experiment lasts for ten rounds or twenty or a hundred, people will start defecting (contributing less) in the final few rounds. Presumably this is because they know that there will be less opportunity for them to get punished, so they maximize their short term gains.

Now, let’s say you’re starting a religion, and you want to influence people’s behaviors. The first thing you do is you set up a system of rewards and punishments (e.g., heaven and hell). Next, let’s say that you want to be able to convert people. Well, one thing you might do is set up a reset button, say, in the form of forgiveness. This allows you to go up to someone who has not been following your rules, explain to them about the system of rewards and punishments, and tell them that they have the chance not to be punished for their past behavior if they ask for forgiveness and act right moving forward.

This structure sets up a well known issue facing Christianity. In principle, one could completely disregard all of the rules, and then repent at the last minute. If your goal is to get people to act right all the time, one thing you can do is introduce uncertainty about when the reward or punishment is going to be doled out. In fact, this seems to be the explicit goal in many of the relevant passages.

Matthew 24:43-44 compares the second coming to having a thief break into your house:

but understand dis: if teh ownr ov teh houz had known at wut tiem ov nite teh thief wuz comin, he wud has kept watch an wud not has let his houz be brokd into. so u also must be ready, cuz teh son ov man will come at an hour when u do not expect him.

“At that tyme the couch of the cieling will be like 10 gurlz who can has some flashlites and go meetz teh man at teh door. 5 wur stoopid and 5 wur not stoopid. Teh stoopid gurlz gotz flashlites, but no baterys. Teh not stoopid onez brot baterys. Teh man wuz gonna be rly late, n tey al took a nap.

“In teh night some dood yelld: ‘It’s teh man! Go meets him!’

“Then al teh gurlz wok up n turnd on teh flashlites. Teh stoopid gurlz said to teh not stoopid gurlz: ‘I can has ur baterys? Mine r dead.’

“‘No’ teh not stoopid gurlz said ‘These r mah baterys! Go buys some.’

“But wile tey wur gone buyin teh baterys, teh man arived. Teh not stoopid gurlz went in wit teh man to his crib to parteh n tey close teh door.

“Latr teh stoopid gurlz came. ‘Dood!’ tey said ‘We r outsid r door, waitin for u to let us in!’

“But teh man said ‘Who r u? Go away, this is mah parteh!’

“So keep redy for teh couch of the cieling, cus u don’t kno wen Jebus is comin bak.

So, the whole thing seems structured to deal with this aspect of human nature that has been shown by lots of different economics experiments, but is well known to you from everyday life, as it was well known to the people writing the new testament two thousand years ago: people will cheat if they think they can get away with it.

|

| Bad behavior is something that you can get away with right up until the point where you can’t. |

Selten, R., & Stoecker, R. (1986). End behavior in sequences of finite Prisoner’s Dilemma supergames A learning theory approach Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 7 (1), 47-70 DOI: 10.1016/0167-2681(86)90021-1

Nice post. Very interesting.